Using “switch” is not an anti-pattern

Summary

- Switch statements over basic enums have lots of disadvantages

- Many of the limitations can be overcome by using either dynamic dispatch, or the visitor pattern depending on your use case

- In languages that support sum types natively, consider using those instead of the visitor pattern

Introduction

I have seen several articles recently that take the position that switch statements are an anti-pattern in regards to best practice object-orientated programming. In a way, the sentiment is usually fine, but I think that these articles are a bit incomplete and don’t tell the full story. Let’s take a lesson from functional programming to find when using a switch is OK.

I’ll use TypeScript in this article as it supports all of the necessary language features and is usually pretty easy to read.

The argument against switch statements

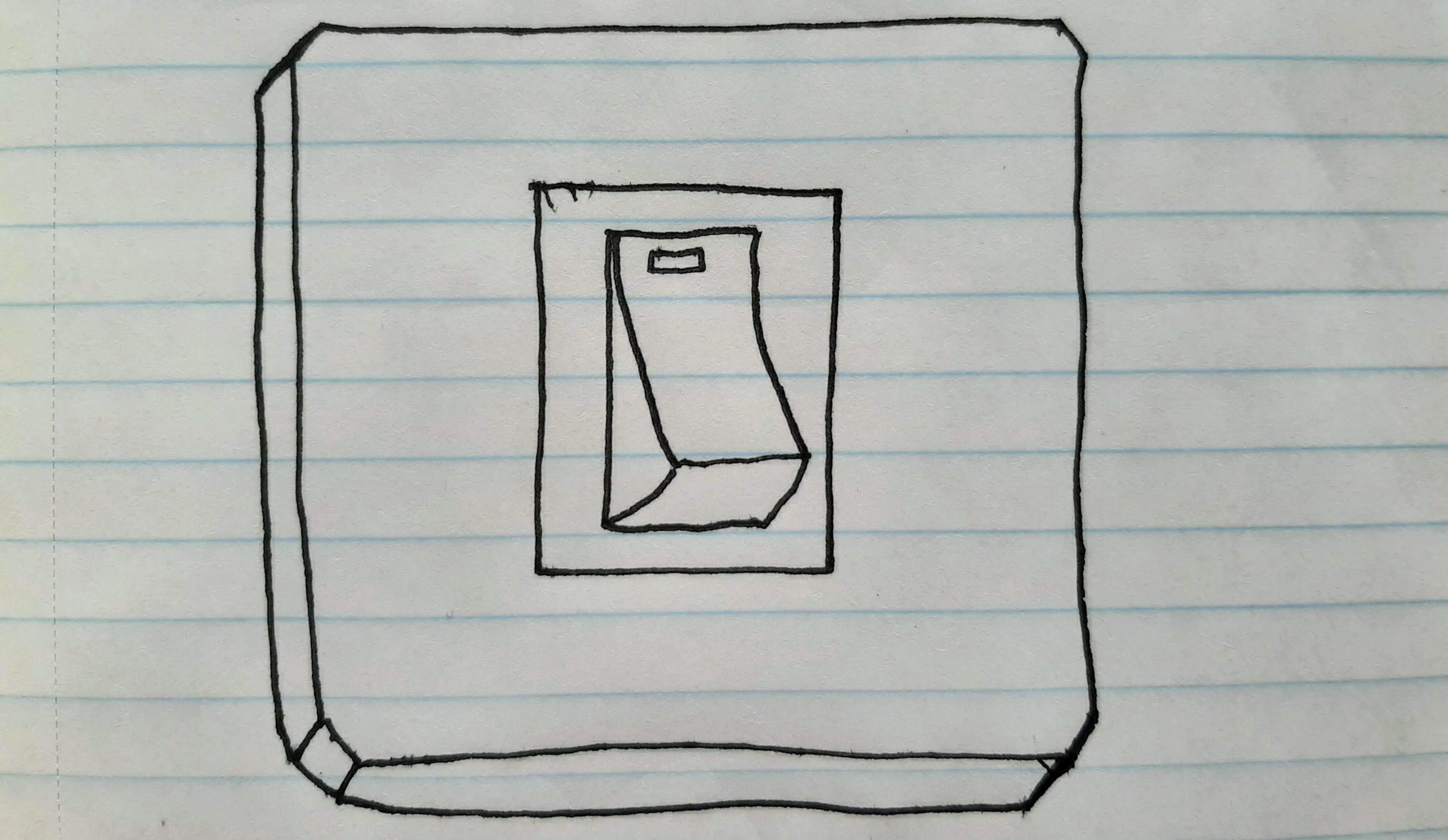

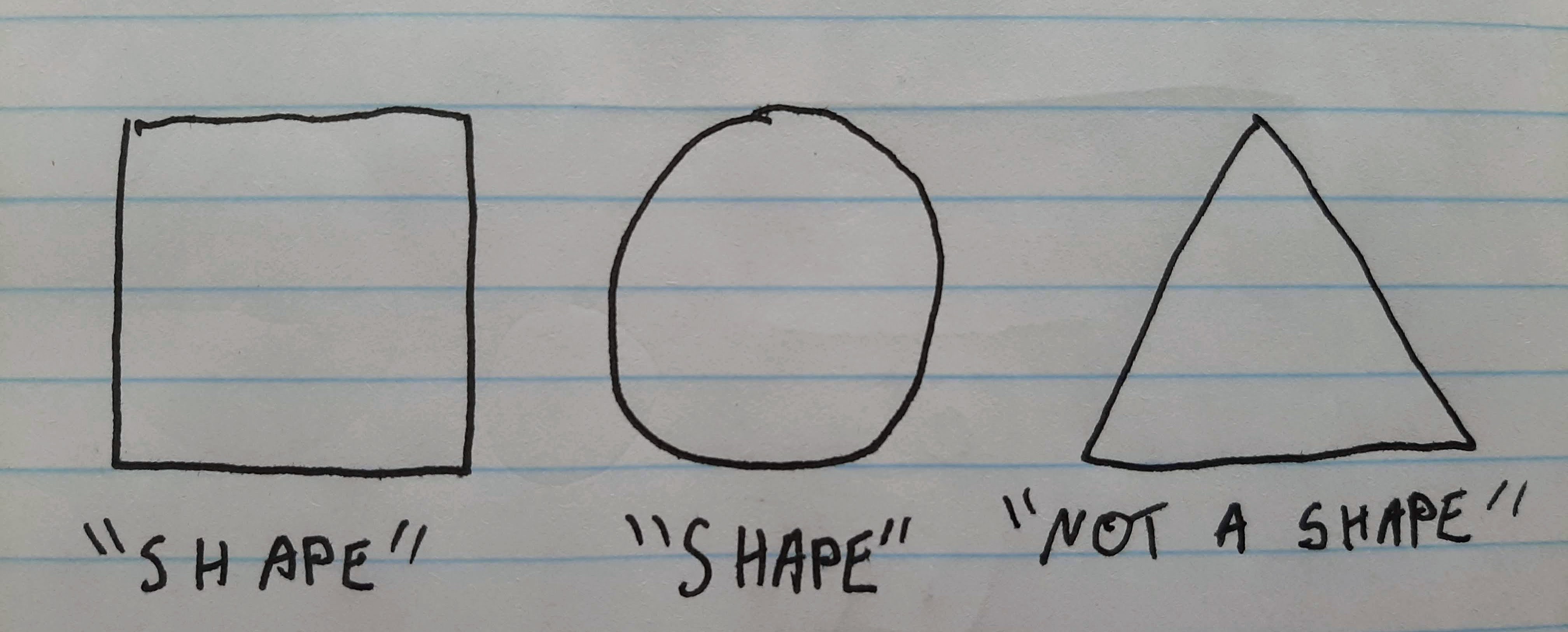

In basic usage switch statements are usually pretty limited, and are used to match against integers, and sometimes strings. Imagine we have two functions draw and area which can either take a unit square (side length 1) or a unit circle (radius 1). Using switch statements the code would look something like this:

enum Shape {

UnitSquare,

UnitCircle

}

const area = (shape: Shape) => {

switch (shape) {

case Shape.UnitSquare:

return 1;

case Shape.UnitCircle:

return Math.PI;

default:

throw new Error("not a shape");

}

}

const draw = (shape: Shape) => {

switch (shape) {

case Shape.UnitSquare:

console.log("drawing a unit square");

return;

case Shape.UnitCircle:

console.log("drawing a unit circle");

return;

default:

throw new Error("not a shape");

}

}

// usage

const doStuff = (shape: Shape) => {

console.log(area(shape));

draw(shape);

}

doStuff(Shape.UnitSquare);

doStuff(Shape.UnitCircle);

There are a number of problems with this code:

- Enums are just integers so you can’t set the side length of the square or the radius of the circle

- If you add another shape, you have to search through all of your code to find switch statements that don’t cover every case. If you miss one you could get runtime errors.

There are probably more reasons why this code is not the best. I will begrudgingly admit it that it has one benefit: as it stands, the code is dead simple to read. There’s no magic and it’s laid out in such a way that it’s very clear what it does.

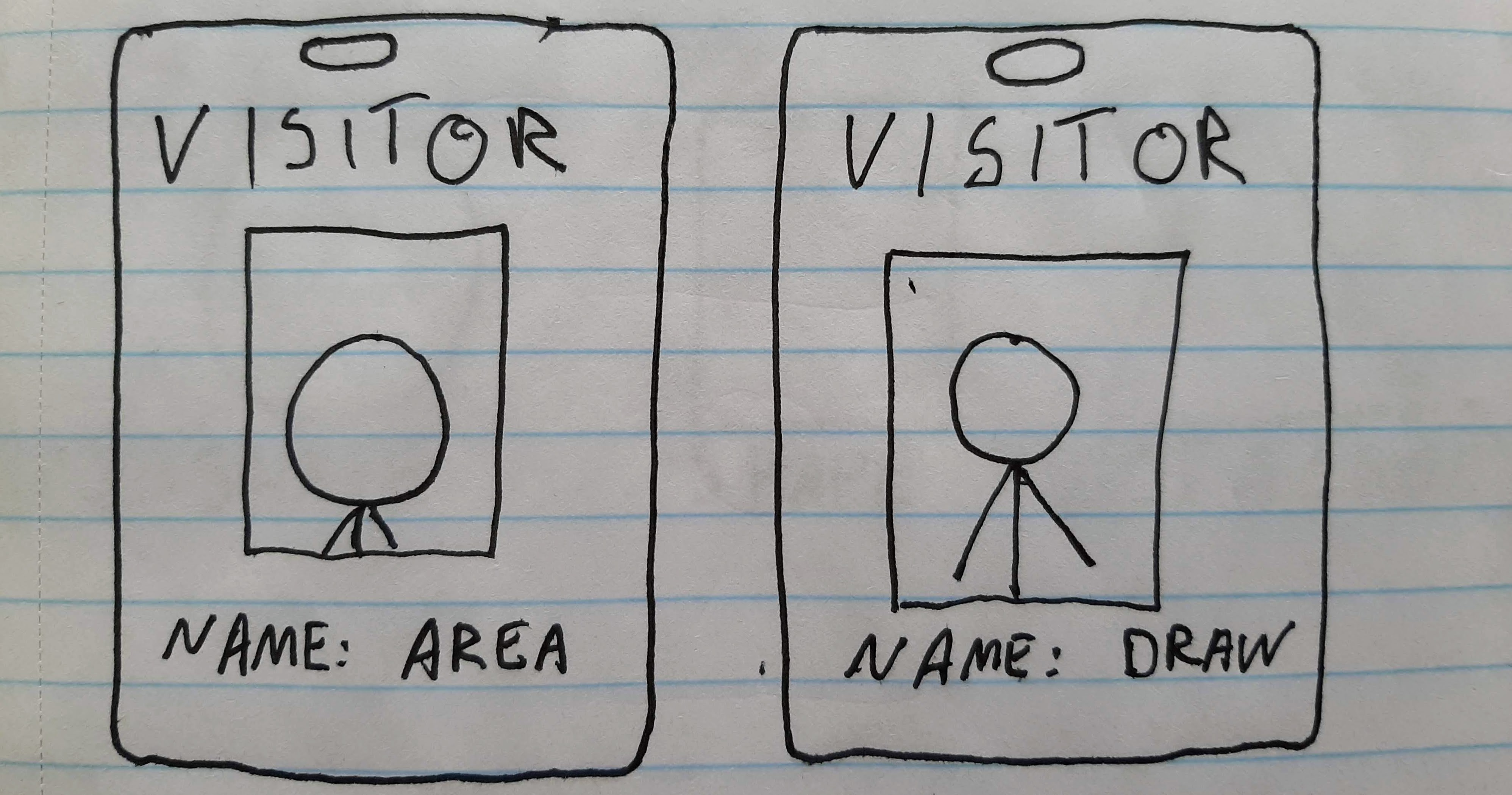

At the moment, we have two functions that both accept two variants each. We could swap this around and have two variants that have two functions each:

interface Shape {

area: () => number;

draw: () => void;

}

class Circle {

private radius: number;

constructor (radius: number) {

this.radius = radius;

}

area() {

return Math.PI * this.radius * this.radius;

}

draw() {

console.log("drawing a circle");

}

}

class Rectangle {

private width: number;

private height: number;

constructor (width: number, height: number) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

area() {

return this.width * this.height;

}

draw() {

console.log("drawing a rectangle");

}

}

//usage

const doStuff = (shape: Shape) => {

console.log(shape.area());

shape.draw();

}

doStuff(new Circle(2));

doStuff(new Rectangle(2, 5));

Instead of having an enum, we provide an interface. The Circle and Rectangle classes implement that interface. This solves both of the original stated aims:

- The

Circlehas a radius, theRectanglenow has a height and width - We can add new types of shapes easily without having to modify switch statements everywhere

So everything is good and we can call it a day right?

Visitors

Before I can head home safe in the knowledge that the second form is the best way to write that particular code I have to ask a question about the future of my program: Am I more likely to add new methods to the Shape interface, or am I more likely to add new types?. For the rest of this article, I will assume that you’re more likely to add new behavior than new types. If this is not your use case, then you can stop reading, use an interface as shown above, and say good riddance to the switch. If you are unsure, then keep reading, you might learn something new.

It’s easy to add more types to an interface: simply define a new class and implement the interface. You don’t have to modify any existing code, you can just add new functionality. However, if you decided that you wanted to add a new method to the Shape interface, then every class that implements Shape needs to be modified.

Compare this to the first example of code where we used a switch statement. If we want to add a new type, then we have to modify all of our switch statements. However if we want to add a new method, then we can just write a new function without modifying any of our existing code.

The first example has the complete opposite problem than the second example does. However, to tackle some of the other limitations of the first example, an OOP enthusiast would probably recognize that we can use the visitor pattern instead:

interface ShapeVisitor<T> {

circle: (circle: Circle) => T;

rectangle: (rectangle: Rectangle) => T;

}

interface Shape {

visit: <T>(visitor: ShapeVisitor<T>) => T;

}

class Circle {

radius: number;

constructor (radius: number) {

this.radius = radius;

}

visit <T>(visitor: ShapeVisitor<T>) {

return visitor.circle(this);

}

}

class Rectangle {

width: number;

height: number;

constructor (width: number, height: number) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

visit <T>(visitor: ShapeVisitor<T>) {

return visitor.rectangle(this);

}

}

const area: ShapeVisitor<number> = {

circle: (circle) => Math.PI * circle.radius * circle.radius,

rectangle: (rectangle) => rectangle.width * rectangle.height

}

const draw: ShapeVisitor<void> = {

circle: (_circle) => console.log("drawing a circle"),

rectangle: (_rectangle) => console.log("drawing a rectangle")

}

// usage

const doStuff = (shape: Shape) => {

console.log(shape.visit(area));

shape.visit(draw);

}

doStuff(new Circle(2));

doStuff(new Rectangle(2, 5));

The visitor pattern is quite complicated, but it does the job.

- The circle has a radius, and the rectangle has side lengths

- New functionality can be added without modifying existing code

- (Bonus benefit!) If we add a new variant (say we add a triangle), then the compiler will point out all the visitors where we need to change our code and won’t compile until we have fixed it.

The the visitor pattern is actually a page taken out of the functional programming book: it is the church encoding for sum types in lambda calculus in disguise. That sounds like gibberish, but what that means for us humans is that we can write the visitor example with much more brevity. Note that I do not condone the use of church encoding in useful programs, but want to include it as a demonstration of how unreadable it is:

interface ShapeVisitor<T> {

circle: (radius: number) => T;

rectangle: (width: number, height: number) => T;

}

interface Shape {

<T>(visitor: ShapeVisitor<T>): T;

}

const Circle = (radius: number): Shape =>

({ circle }) => circle(radius);

const Rectangle = (width: number, height: number): Shape =>

({ rectangle }) => rectangle(width, height);

const area: ShapeVisitor<number> = {

circle: (radius) => Math.PI * radius * radius,

rectangle: (width, height) => width * height

}

const draw: ShapeVisitor<void> = {

circle: () => console.log("drawing a circle"),

rectangle: () => console.log("drawing a rectangle")

}

// usage

const doStuff = (shape: Shape) => {

console.log(shape(area));

shape(draw);

}

doStuff(Circle(2));

doStuff(Rectangle(2, 5));

In this example we ditch classes, and use closures instead. This has all of the advantages of the visitor pattern, but is even more unreadable. Church encoding is not a great way to program.

Sum types

In the above examples we mentioned “sum types”. A sum type is something that can be one thing or another. For example, boolean is a sum type of true and false because it can either be true or false. Shape is a sum type too: it can either be a Circle or a Rectangle.

We used the “Church encoding” for sum types in the above example. The Church encoding is one method you can use when your language doesn’t support sum types natively. Luckily for us, TypeScript does support sum types, so we should prefer that:

type Shape = Circle | Rectangle

interface Circle {

variant: 'circle';

radius: number;

}

const Circle = (radius: number): Circle => {

return { variant: 'circle', radius };

}

interface Rectangle {

variant: 'rectangle';

width: number;

height: number;

}

const Rectangle = (width: number, height: number): Rectangle => {

return { variant: 'rectangle', width, height };

}

const unreachable = (_x: never) => {};

const area = (shape: Shape) => {

switch (shape.variant) {

case 'circle':

return Math.PI * shape.radius * shape.radius;

case 'rectangle':

return shape.width * shape.height;

default:

return unreachable(shape);

}

}

const draw = (shape: Shape) => {

switch (shape.variant) {

case 'circle':

console.log("drawing a rectangle");

return;

case 'rectangle':

console.log("drawing a circle");

return;

default:

return unreachable(shape);

}

}

// usage

const doStuff = (shape: Shape) => {

console.log(area(shape));

draw(shape);

}

doStuff(Circle(2));

doStuff(Rectangle(2, 5));

The funny unreachable function is used as a static assertion. The program will not compile if there is a valid code path that reaches the unreachable function. We no longer need to throw an error in the switch branches because the compiler can statically determine that the default branch is never executed. This means that if you added a new variant (like a triangle) the program won’t compile until you fix all of the relevant switch statements.

Conclusion

We have come full circle. We took a long journey but we are back at a switch statement. The above code essentially has all the benefits of the original visitor example, because semantically they describe the same thing.

- We started off with a switch on an enum and found it had lots of disadvantages

- We could fix those disadvantages by using the visitor pattern

- The visitor pattern is a way to describe sum types using Church encoding in languages that don’t support them natively

- In languages that support sum types, consider using them directly

The differences between the first and last examples are:

- The switch statement matches on the variants of a sum type rather than a basic

enum - The switch statement is exhaustive due to the

unreachablefunction

So if your language supports sum types and you think you’re more likely to add new functionality to existing classes than you are to add a new types, consider using switch.

Parting Note

In languages that don’t support sum types natively, don’t be afraid to use a visitor if you were thinking about using a switch statement. After all, it is a well established design pattern. If you find yourself needing to branch based on type, or if you need to use downcasting, then consider using a visitor as an alternative.

This post was originally posted on Andrew’s Notepad

typescript

programming

object orientated programming

functional programming

javascript

sum types

type theory

visitor pattern

church encoding