Summary

- For the majority of code, shared mutability is usually not required.

- We cannot have sharing, mutability and “internal consistency”. A program that tries to have all three is provably incorrect.

- If we want sharing, and mutability but do not need “internal consistency”, we can use a file, a database handle, a mutex, or any other similar structure.

- If we need mutability, and “internal consistency” but do not need sharing, we can have all modifications go through a common ancestor.

- If we need sharing, and “internal consistency” but not mutability, we can freeze our data, or have persistent data structures.

The problem with shared mutability.

Safe Rust provides us with some guarantees: namely safe memory access, no undefined behavior, and no data races. In addition to this, safe Rust makes it difficult (but not impossible) to have memory leaks, mutate structures through immutable references, or create memory cycles.

I’ll start by saying that these things are made difficult to do because they are difficult to reason about. Safe rust introduces some resistance so that programmers are more likely to design their programs in such a way that they are more likely to be correct.

If we ignore IO or interior mutability for a moment, safe Rust has property that whenever you hold an immutable reference to an object, the holder of the reference doesn’t know (or doesn’t care) if other structures also hold a reference to it. If you wanted to, you could clone the data and it would make no difference to the program.

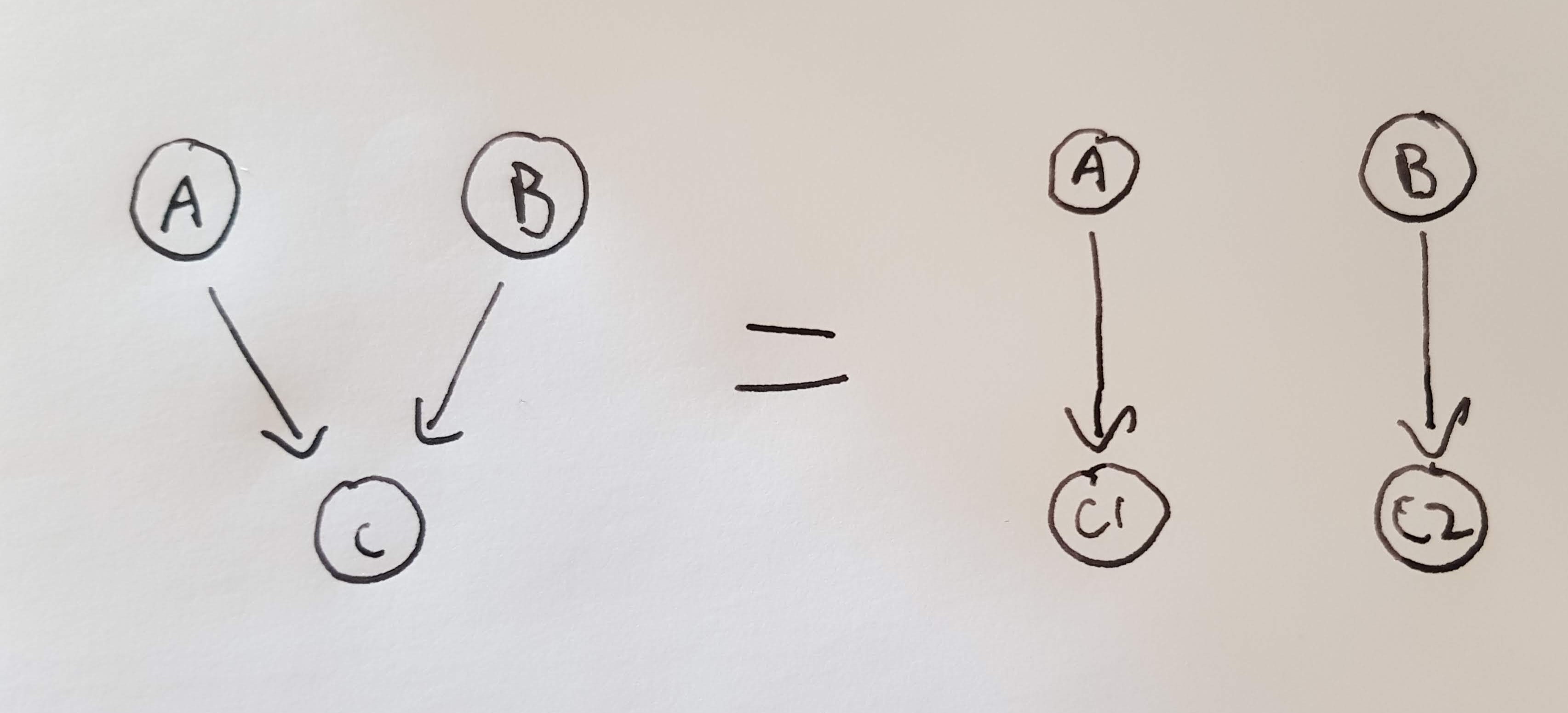

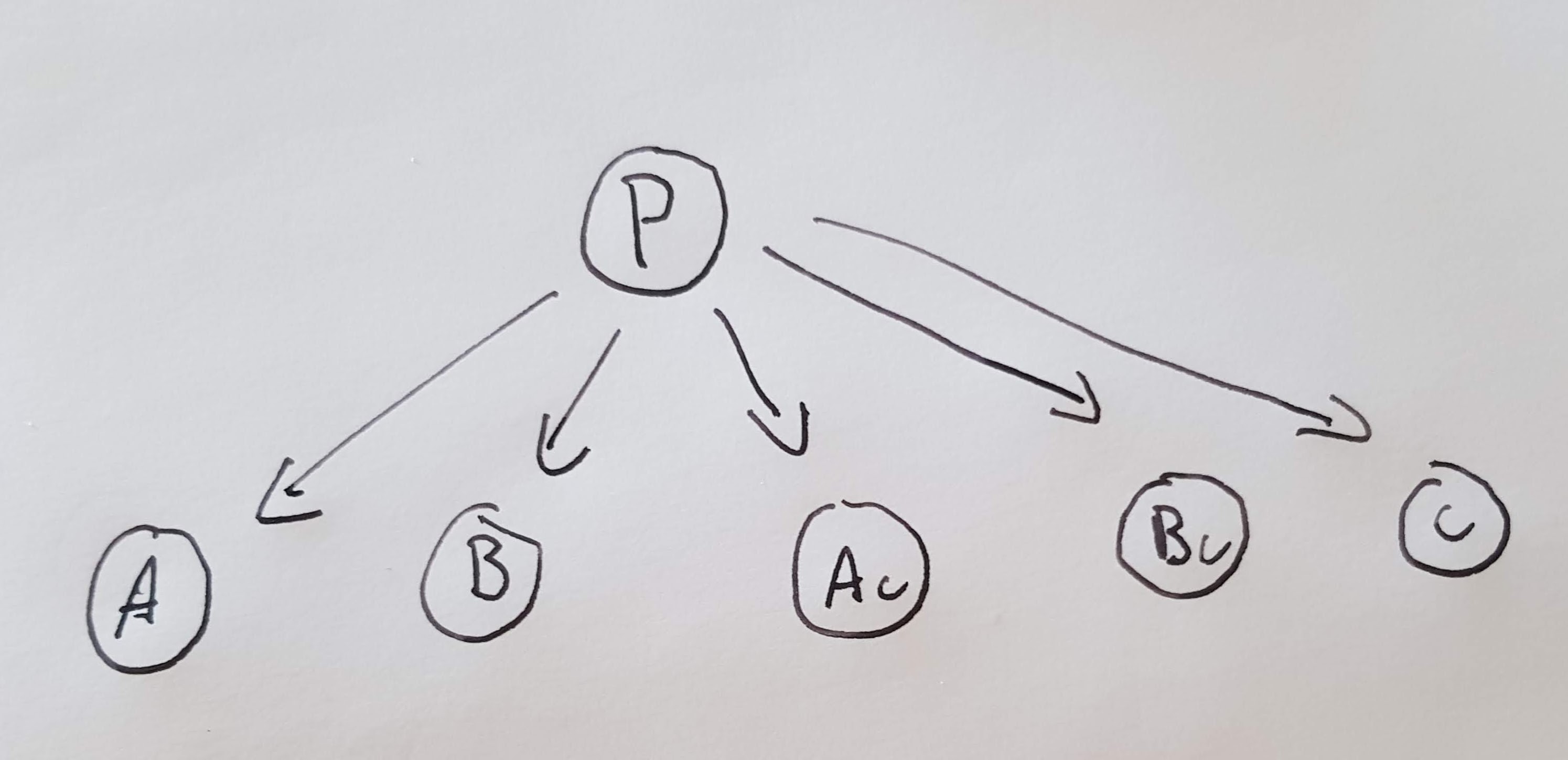

To illustrate this point, let’s draw a diagram where circles are objects, and an arrow means that an object “knows” about the other. We have objects A and B which are regular objects that don’t know about each other. We also have object C for “Child”. Both A and B know about C, but not necessarily the other way around. We won’t talk about the case where A and B know about each other, because then we would have a circular reference, which is beyond the scope of this article.

As long as you don’t try to change the child C, it doesn’t matter if you had your own copy or not. The program behaves exactly the same way if every object had their own copy of C, or if they all pointed to the same one.

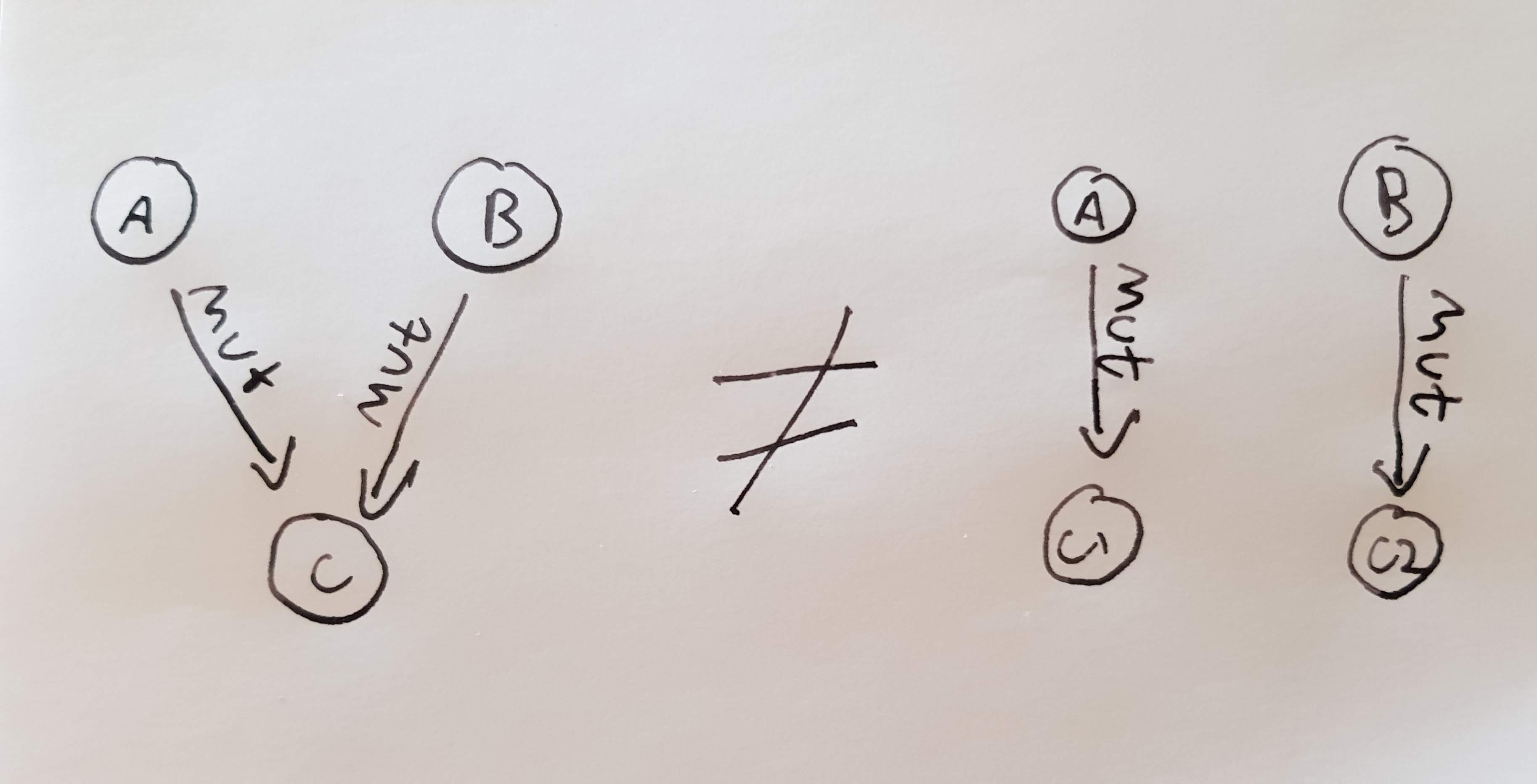

However, this makes it difficult when you want to write a program with shared mutability. Specifically when you have an object with multiple owners, when one owner changes the data, we want the other owner to be able to see that the data has changed. We now require that the owners have a reference to the same object.

This presents us with a problem. If we need to ask B about something that depends on C, then we have to recalculate it every single time because it could have been changed by A. As far as B is concerned, C could be anything because B doesn’t know about A.

If this is your use case, and C is a database connection, a webpage, a file, a mutex, or some other kind of IO. then you don’t have to continue reading. You will have to refresh the webpage, or perform a new database request, or obtain the mutex lock if you want your data to be up to date (which I will refer to now as “internally consistent” or just “consistent”). If you don’t trust the data to be unmodified between requests you have no choice but to recalculate every time:

struct A<'c> {

value: u32,

// we consider the child volatile, so we have to check it every time.

child: &'c std::cell::RefCell<C>

}

impl<'c> A<'c> {

// we need to calculate this every time we query it.

fn total (&self) -> u32 {

self.value + self.child.borrow().value

}

}

struct B<'c> {

value: u32,

child: &'c std::cell::RefCell<C>

}

impl<'c> B<'c> {

// we need to calculate this every time we query it.

fn difference (&self) -> u32 {

self.value - self.child.borrow().value

}

}

struct C {

pub value: u32,

}

fn main () {

let c = std::cell::RefCell::from(C {value: 10});

let a = A {value: 15, child: &c};

let b = B {value: 30, child: &c};

println!("A's total: {}", a.total()); // 25

println!("B's difference: {}", b.difference()); // 20

c.borrow_mut().value = 5;

println!("A's total: {}", a.total()); // 20

println!("B's difference: {}", b.difference()); // 25

}

The “Internal Consistency Problem”

If this is not your use case, and you want your data to remain consistent without having to recalculate for C every single time, then we need to make some changes.

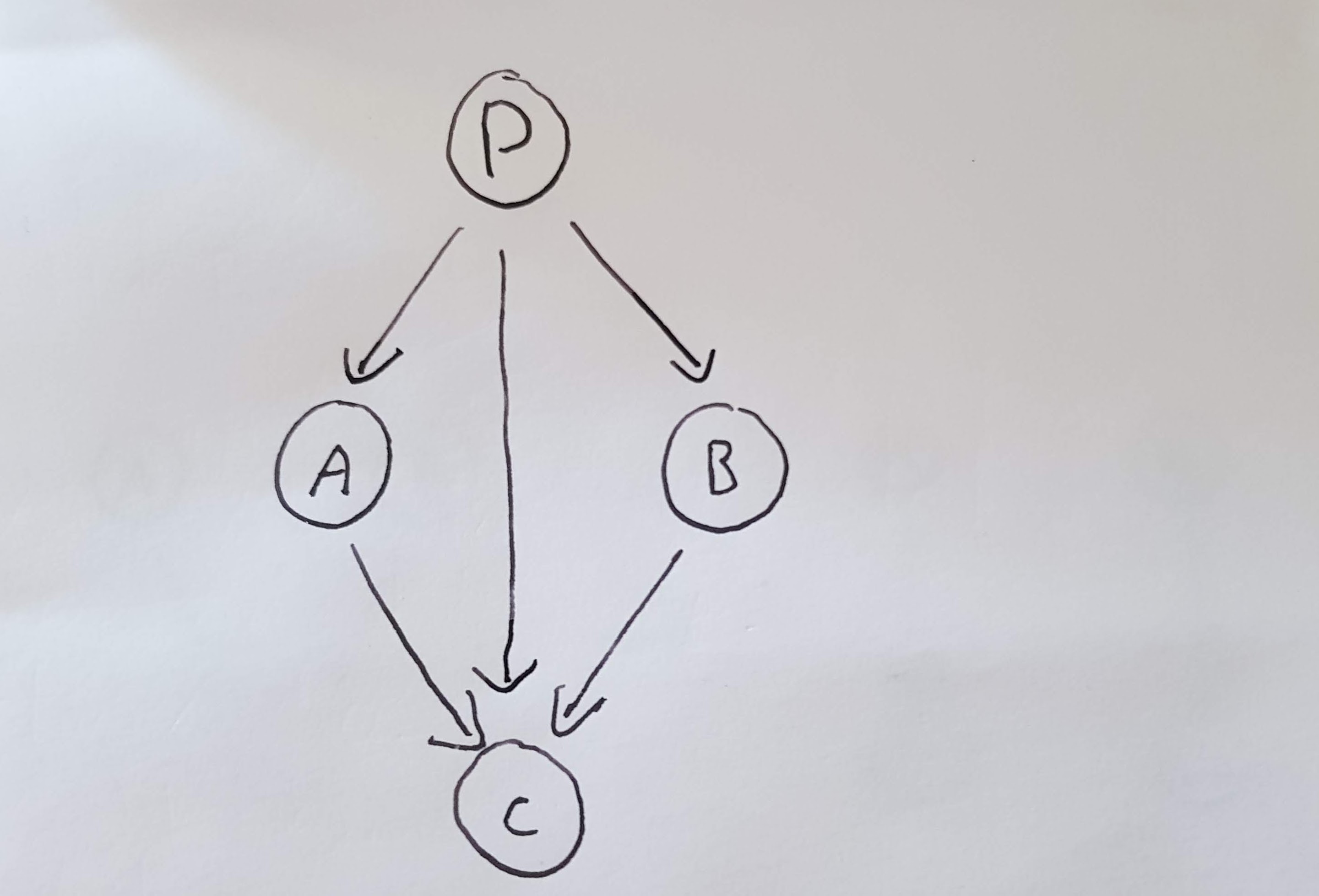

In this case, A and B are going to need to be notified when C changes, so they know that their old data is no longer valid. In order to do this, there must be some object, let’s say P for “Parent” which knows about A, B, and the common child C.

Any time we need to change the child C, we go though the parent P. That way P can tell both A and B that C has changed, and our data is internally consistent. We’re not allowed to modify C through A or B anymore, because A and B don’t know about each other.

We now realize that A and B don’t need to know about C. Every time C changes, P tells A and B all the necessary information about the change. A and B are then updated accordingly. In fact, A and B can’t know about C. If they knew about C, then we have the same problem that we started with, except now we have shared mutability between three objects not just two.

Now P is now the only object which has mutable access to C. We solved the problems of shared mutability by not having sharing. We had to make the changes above if we wanted our data to remain internally consistent. If we take this to the extreme, we can say that A, B and P are the same object. Below is an implementation:

struct P {

a: u32,

b: u32,

c: u32,

a_plus_c: u32,

b_minus_c: u32,

}

impl P {

fn new (a: u32, b: u32, c: u32) -> Self {

P {

a: a, b: b, c: c,

a_plus_c: a + c,

b_minus_c: b - c,

}

}

fn set_c (&mut self, c: u32) {

self.c = c;

self.a_plus_c = self.a + self.c;

self.b_minus_c = self.b - self.c;

}

// we don't need to recalculate each time.

fn total(&self) -> u32 {

self.a_plus_c

}

fn difference(&self) -> u32 {

self.b_minus_c

}

}

fn main () {

let mut p = P::new(15, 30, 10);

println!("A's total: {}", p.total()); // 25

println!("B's difference: {}", p.difference()); // 20

p.set_c(5);

println!("A's total: {}", p.total()); // 20

println!("B's difference: {}", p.difference()); // 25

}

We draw the conclusion that shared mutability and internal consistency are mutually exclusive. We have to choose one or the other. Choosing both at the same time will lead to incoherent programs, and we have no reason to be writing incoherent programs.

Prevent mutability.

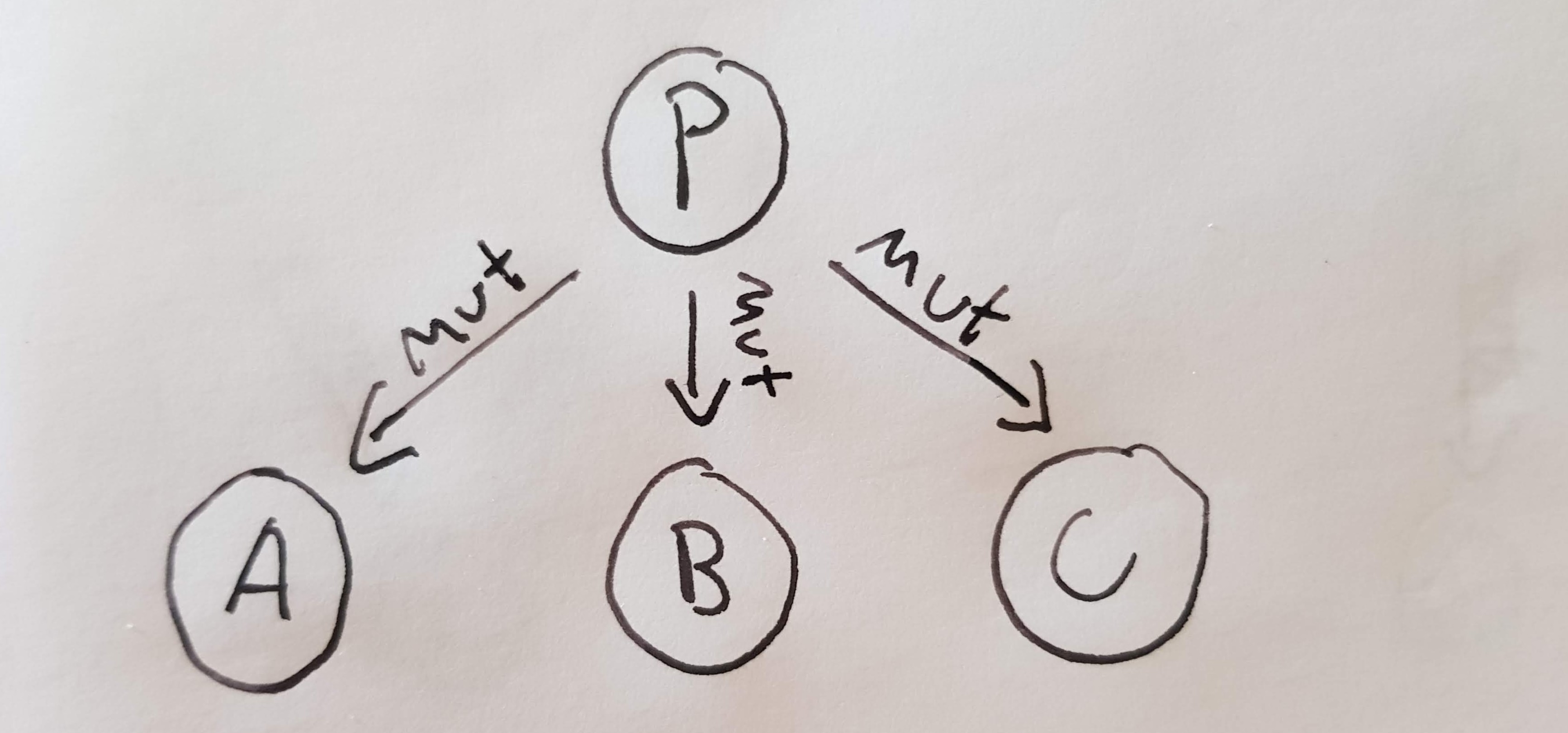

We have already seen one solution to the “internal consistency problem”: make all modifications go through a common ancestor. That basically means we get rid of the “sharing” part of “shared mutability”. We can also try rid ourselves of the “mutability” part of “shared mutability”.

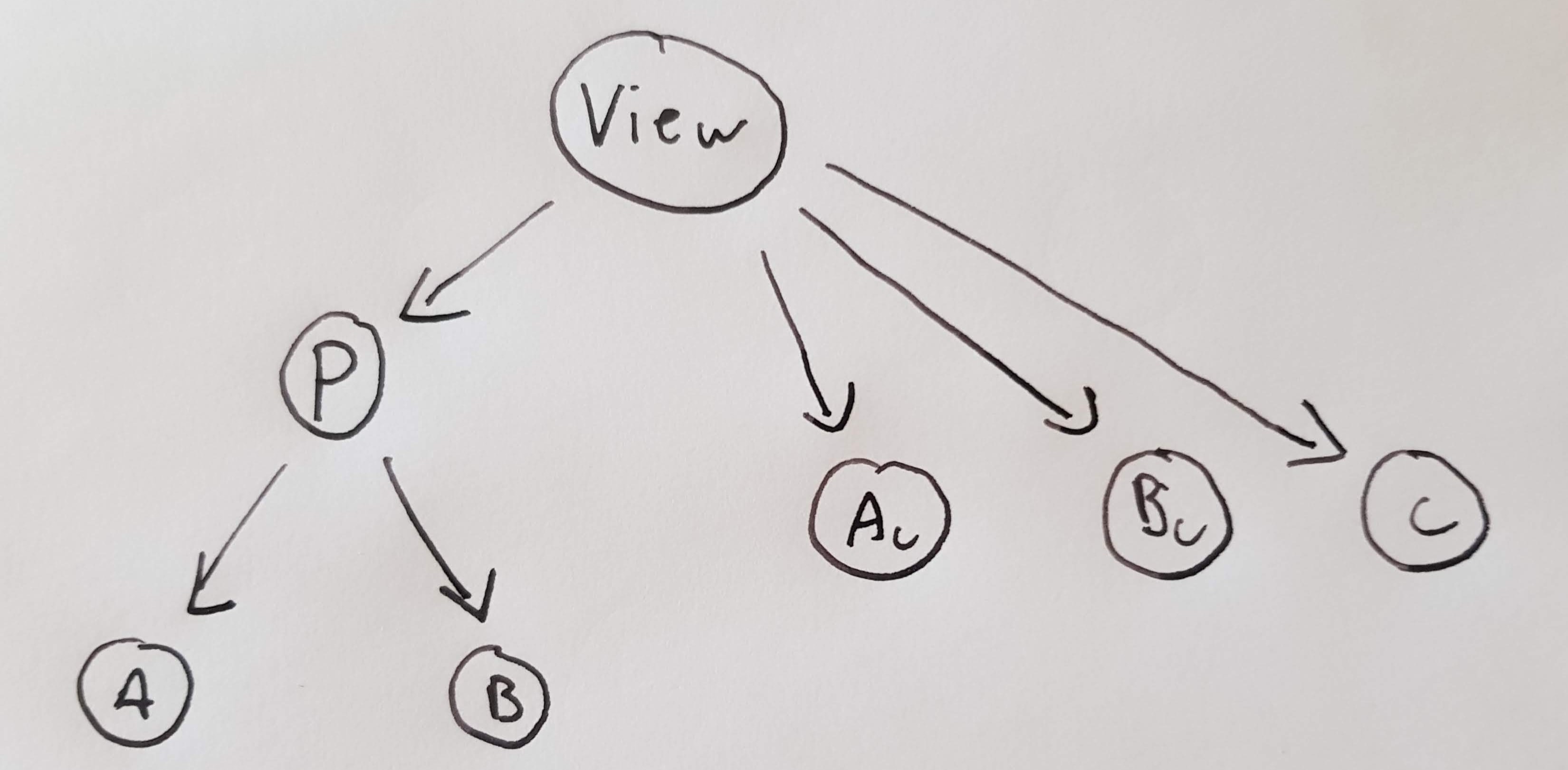

First of all we split our objects into two parts. The part of the object that doesn’t depend on C and the part that does. We’ll use subscript to denote that the object depends on C.

We know that A does not depend on C, so if C changes, we don’t have to notify A. This is the same with B. We can make any modifications we like to A, B and C, and they’ll all be correct. Ac and Bc however, have the same problems that we had before.

Instead of trying to keep Ac and Bc up to date all the time every time we change C, we can freeze P to stop it from becoming modified, then (and only then), we create Ac and Bc. As long as P and it’s children remain unmodified, Ac and Bc will be correct.

We can freeze an object in Rust by taking an immutable reference of it. The following code implements this idea:

struct P2 {

pub a: u32,

pub b: u32,

pub c: u32,

}

struct View<'p> {

_lock: &'p P2,

total: u32,

difference: u32,

}

impl<'p> View<'p> {

fn new(parent: &'p P2) -> Self {

View {

_lock: parent,

total: parent.a + parent.c,

difference: parent.b - parent.c,

}

}

fn total(&self) -> u32 {

self.total

}

fn difference(&self) -> u32 {

self.difference

}

}

fn main() {

let mut p2 = P2 {a: 15, b: 30, c: 10};

{

// p2 is locked to mutable access for the duration of 'p.

let view = View::new(&p2);

println!("A's total: {}", view.total()); // 25

println!("B's difference: {}", view.difference()); // 20

// The lock is released here

}

p2.c = 5;

{

// p2 is locked to mutable access for the duration of 'p.

let view = View::new(&p2);

println!("A's total: {}", view.total()); // 25

println!("B's difference: {}", view.difference()); // 20

// The lock is released here

}

}

Conclusion.

Sometimes your program design calls for some shared mutability. Unfortunately, it is impossible for arbitrary data to remain consistent in the presence of shared mutability. We have to choose to get rid of one of sharing, mutability, or the expectation of consistency. I have presented two ways to structure programs which solve typical use cases for shared mutability, whilst still remaining correct.

In the next article, I will use the knowledge discovered here to discuss making arbitrary directed acyclic graphs in Rust.

This post was originally posted on Andrew’s Notepad

Rust

graph

acyclic

mutability

references