Summary

- A persistent data structure can easily keep track of previous versions of itself with little overhead.

- A regular data structure can be converted into a persistent one by replacing instances of

BoxwithRc, and replacing mutable dereferences withRc::make_mut. - The resulting structure is both more performant and uses less memory if you plan on performing lots of clones.

What is a persistent data structure?

Data structures are persistent when they can keep track of all of their old states. Every time a modification is made, a new structure is created instead of modifying the original data. Persistent data structures are often referred to as immutable, because the original data is left untouched.

A naive persistent version of any data structure is trivial to make: Just clone the entire structure every time a change is made, and then commit the relevant changes to the new version. That way the old version is kept. However, for anything larger than a trivially small structure, this is going to be problematic.

There is a better way to create persistent data structures. Instead of copying the entire structure each time a modification is made, only the parts that have been modified need to be copied. The rest of the data is shared between old and new versions. This can be performed through the use of clone-on-write pointers.

Rust provides three clone-on-write pointers in the standard library: Cow, Rc and Arc. Cow only sometimes owns it’s own data, so is not suitable for these kinds of data structure. In this article, Rc will be used, but Arc is equally valid.

Note that in Rust, instead of creating a new version every time a structure is modified, the persistent structures will have both a cheap clone function, and will share memory with older versions of themselves, but will otherwise share an API with their non-persistent counterparts.

Example 1: A singly linked list.

Let’s get stuck into into it. Consider a simple implementation of a non persistent singly linked list using Box. Mind you, that I don’t recommend using this kind of data structure for everyday use for well known reasons.

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub enum ListBox<A> {

Nil,

Cons(A, Box<ListBox<A>>),

}

impl<A> ListBox<A> {

pub fn new() -> Self {

ListBox::Nil

}

pub fn cons(&mut self, elem: A) {

let tail = std::mem::replace(self, ListBox::Nil);

let mut list = ListBox::Cons(elem, Box::new(tail));

std::mem::swap(self, &mut list)

}

pub fn uncons(&mut self) -> Option<A> {

let list = std::mem::replace(self, ListBox::Nil);

match list {

ListBox::Nil => None,

ListBox::Cons(elem, mut tail) => {

std::mem::swap(self, &mut tail);

Some(elem)

}

}

}

}

Seems simple enough. new creates an empty list and cons adds an element to a pre-existing list. To read from the list, uncons removes the first element. Essentially, this list acts like a stack where cons is push and uncons is pop.

To test this list, a dummy structure is used which implements Clone. This can be used to track how many clones are performed at runtime:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct CloneTracker(u32);

impl Clone for CloneTracker {

fn clone(&self) -> Self {

println!("Cloning {}...", self.0);

CloneTracker

}

}

The list works as expected:

let mut list_box = ListBox::new();

for i in 0..10 {

list_box.cons(CloneTracker(i));

}

// prints "Cloning x..." ten times

let _clone = list_box.clone();

list_box.cons(CloneTracker(20));

assert_eq!(list_box.uncons(), Some(CloneTracker(20)));

for i in (0..10).rev() {

assert_eq!(list_box.uncons(), Some(CloneTracker(i)));

}

assert_eq!(list_box.uncons(), None);

The list is cloned to keep an older version of it for later. Every element in the list is cloned which is confirmed by the output produced by the CloneTracker.

To make the list persistent, two modifications are required: Firstly, change any Box to an Rc. Secondly, whenever a Box was mutably dereferenced in the old code, replace it with Rc::make_mut:

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub enum List<A> {

Nil,

Cons(A, Rc<List<A>>),

}

impl<A: Clone> List<A> {

pub fn new() -> Self {

List::Nil

}

pub fn cons(&mut self, elem: A) {

let tail = std::mem::replace(self, List::Nil);

let mut list = List::Cons(elem, Rc::new(tail));

std::mem::swap(self, &mut list)

}

pub fn uncons(&mut self) -> Option<A> {

let list = std::mem::replace(self, List::Nil);

match list {

List::Nil => None,

List::Cons(elem, mut tail) => {

std::mem::swap(self, Rc::make_mut(&mut tail));

Some(elem)

}

}

}

}

To confirm that the list is correct, it is tested:

let mut list = List::new();

for i in 0..10 {

list.cons(CloneTracker(i));

}

// prints "Cloning x..." once!

let _clone = list.clone();

list.cons(CloneTracker(20));

assert_eq!(list.uncons(), Some(CloneTracker(20)));

for i in (0..10).rev() {

// prints "Cloning i..."

assert_eq!(list.uncons(), Some(CloneTracker(i)));

}

assert_eq!(list.uncons(), None);

This works almost identically to the previous example. The difference is that the clones are performed at different times. In the first example The clones are performed at the clone call. In the second example, the clones are delayed until the list is actually modified. You can confirm that this is the case by commenting out the lines in question.

It turns out that the original list and its clone share the majority of the data. During a modification, only the data that needs to be modified is cloned, and the rest remains shared. In essence, each list pretends that it holds a clone of all of its own data, but in reality, the clone operation only occurs when the data is written.

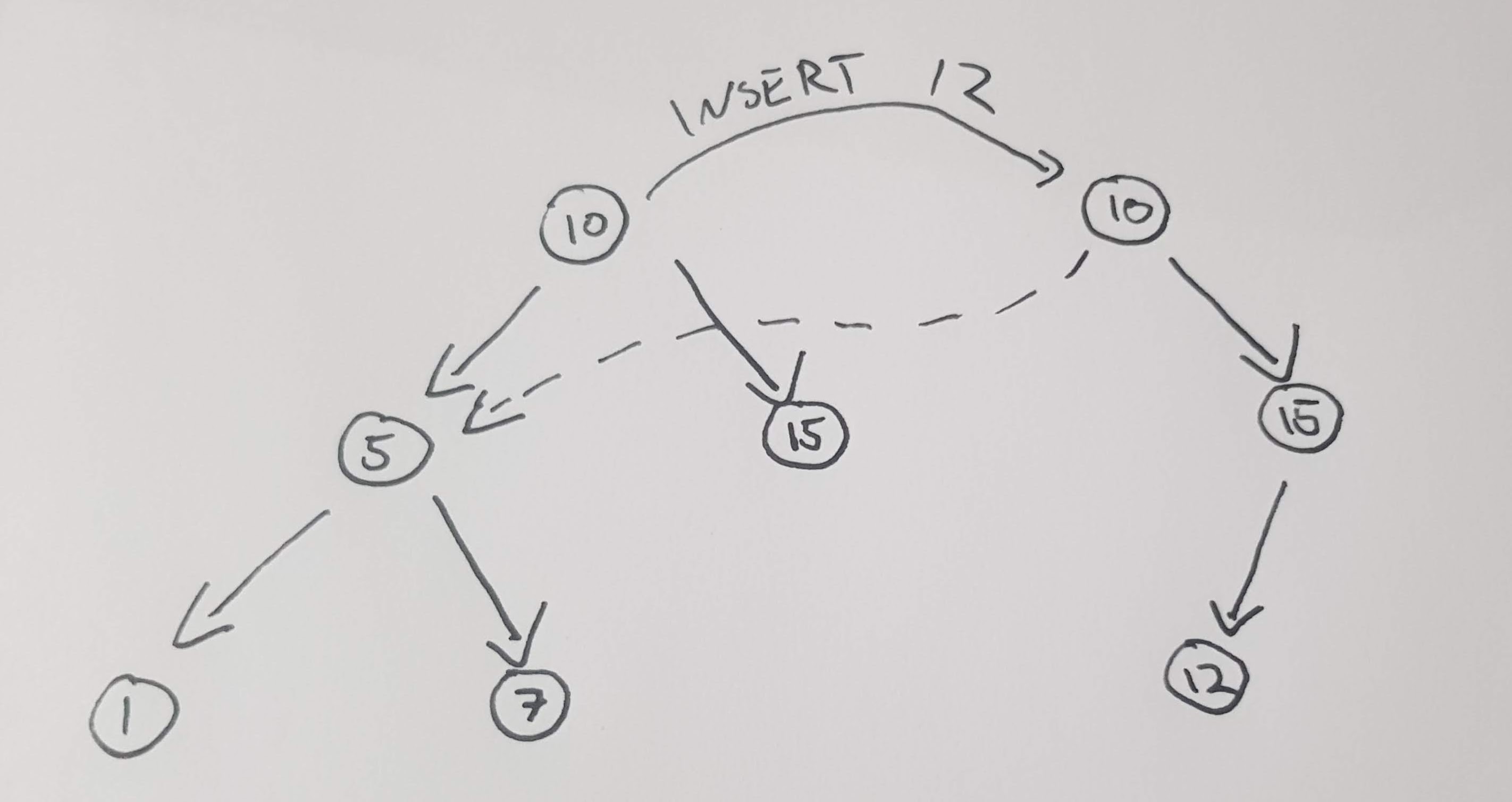

Example 2: A tree.

Next consider a simple implementation of a tree using Box. For brevity, this will not be a balanced tree. Again, this implementation is overly simplified and I would not recommend using this structure in practice:

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum TreeBox<A> {

Leaf,

Node(Box<TreeBox<A>>, A, Box<TreeBox<A>>),

}

impl<A: Ord> TreeBox<A> {

pub fn new() -> Self {

TreeBox::Leaf

}

pub fn singleton(value: A) -> Self {

TreeBox::Node(Box::new(TreeBox::Leaf), value, Box::new(TreeBox::Leaf))

}

pub fn insert(&mut self, input: A) {

match *self {

TreeBox::Leaf => *self = TreeBox::singleton(input),

TreeBox::Node(ref mut left, ref value, ref mut right) => {

if &input < value {

left.insert(input);

} else if &input > value {

right.insert(input);

}

}

}

}

pub fn find (&self, elem: &A) -> bool {

match *self {

TreeBox::Leaf => false,

TreeBox::Node(ref left, ref value, ref right) => {

if elem < value {

left.find(elem)

} else if elem > value {

right.find(elem)

} else {

true

}

}

}

}

}

new creates an empty tree and singleton creates a tree with a single element. insert is used to build a tree by inserting elements, and find will return true if the element exists in the tree. Most of the implementation of a tree is omitted, but you get the idea.

The tree can be tested to ensure that it works correctly:

extern crate rand;

use rand::seq::SliceRandom;

let mut tree = TreeBox::new();

// even numbers only.

let mut numbers: Vec<u32> = (0..50).map(|x| x * 2).collect();

numbers.shuffle(&mut rand::thread_rng());

for num in numbers.clone() {

tree.insert(CloneTracker(num));

}

// prints "Cloning x..." 50 times.

let _clone = tree.clone();

tree.insert(CloneTracker(47));

tree.insert(CloneTracker(15));

for num in numbers {

assert_eq!(tree.find(&CloneTracker(num)), true);

}

assert_eq!(tree.find(&CloneTracker(47)), true);

assert_eq!(tree.find(&CloneTracker(15)), true);

Note that when the clone operation is performed, all of the nodes are cloned. This behaves exactly as you would normally expect. To store an old version of the structure, twice the memory of the original structure is required.

Again, if we make the same modifications: replacing every instance of Box with Rc and using Rc::make_mut every time we want a mutable reference, the structure requires far less cloning:

pub enum Tree<A> {

Leaf,

Node(Rc<Tree<A>>, A, Rc<Tree<A>>),

}

impl<A: Ord + Clone> Tree<A> {

pub fn new() -> Self {

Tree::Leaf

}

pub fn singleton(value: A) -> Self {

Tree::Node(Rc::new(Tree::Leaf), value, Rc::new(Tree::Leaf))

}

pub fn insert(&mut self, input: A) {

match *self {

Tree::Leaf => *self = Tree::singleton(input),

Tree::Node(ref mut left, ref value, ref mut right) => {

if &input < value {

Rc::make_mut(left).insert(input);

} else if &input > value {

Rc::make_mut(right).insert(input);

}

}

}

}

pub fn find (&self, elem: &A) -> bool {

match *self {

Tree::Leaf => false,

Tree::Node(ref left, ref value, ref right) => {

if elem < value {

left.find(elem)

} else if elem > value {

right.find(elem)

} else {

true

}

}

}

}

}

If the exact same test is performed as above, the results are markedly different. The difference only increases as the tree becomes larger.

let mut tree = Tree::new();

// even numbers only.

let mut numbers: Vec<u32> = (0..50).map(|x| x * 2).collect();

numbers.shuffle(&mut rand::thread_rng());

for num in numbers.clone() {

tree.insert(CloneTracker(num));

}

// prints "Cloning x..." only once!

let _clone = tree.clone();

// prints "Cloning x..." a few times.

tree.insert(CloneTracker(47));

// prints "Cloning x..." a few times.

tree.insert(CloneTracker(15));

for num in numbers {

assert_eq!(tree.find(&CloneTracker(num)), true);

}

assert_eq!(tree.find(&CloneTracker(47)), true);

assert_eq!(tree.find(&CloneTracker(15)), true);

During the clone call, only the root node is cloned. During the insertion, only the nodes that have been modified are cloned. This can be confirmed by commenting out the relevant sections of code. The rest of the data is shared between the old version and the new version.

Conclusion

Data structures that involve Box can be converted easily into persistent versions by replacing Box with Rc. These structures easily keep track of their previous state without much overhead. In Rust, this means that the structures have a minimal cost when performing a clone operation, and the clone is performed incrementally as the structure is modified. The performance is greater and the memory usage is smaller for persistent structures than their traditional counterparts if clones are expected often.

This post was originally posted on Andrew’s Notepad

Functional programming

data structures

Rust

Programming