Summary

- Child entities which are both mutable and shared can make any, or all of their parents invalid.

- In freeform shared mutability, we cannot cache any calculation that depends on a shared mutable entity.

- If we limit the scope of sharing to code we trust not to invalidate our cache, then we can cache results as much as we like.

- Limiting the scope of sharing implies that we have some kind of container entity: an Arena.

Interfaces, encapsulation and references.

First of all a disclaimer. I’m going to use the terms such as “interface” and “encapsulation”, and I’m going to define them a little bit differently to normal. It may be a bit strange, but hopefully it will make sense.

Instead of writing some code and trying to fix it, let’s try creating some good code first try. I won’t guarantee that it’s performant, but I’ll settle for (mostly) correct. To do that, we have to somehow prove that our code works. Generally speaking, we start off logical derivation with some definitions.

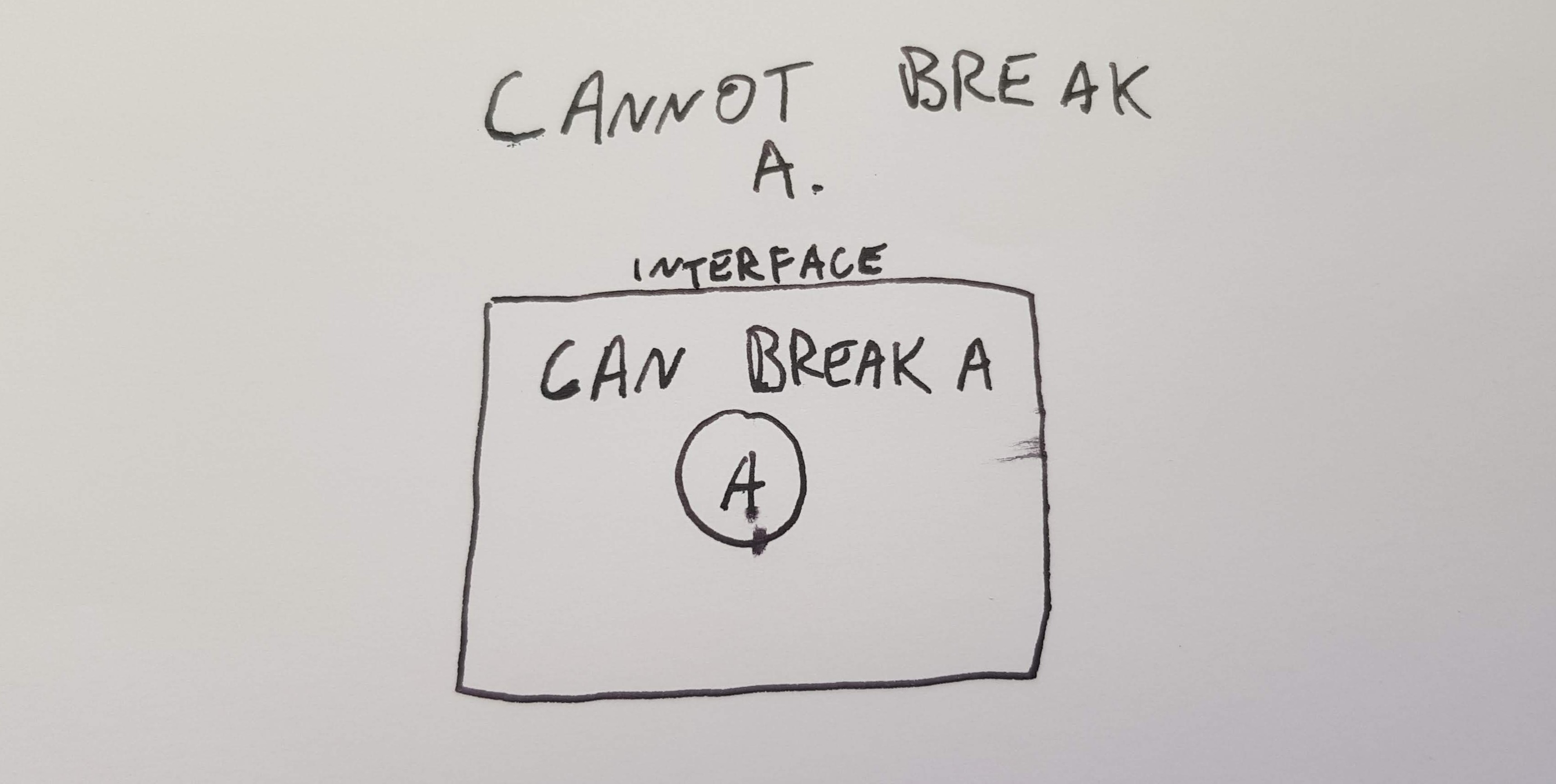

We imagine an entity A which is part of your program. A holds some data, which can either be in a valid state or invalid. If A ever manages to get into an invalid state and stay there, then we say that our program is broken. Sometimes we need to break A temporarily when we are transitioning from two valid states. To ensure that A doesn’t stay broken, we draw a box around it. Code inside the box can break A and code outside the box can’t. A is always valid outside the box. The barrier between the two areas, we’ll call the interface. To make it easy to understand, I’ll call the area inside the box the danger zone and code outside the box the safe zone.

Now I won’t discuss how to construct an interface, or what it should look like. It’s going to be different for every language. Safe to say that we can run any code we like in the safe zone and it will not break A, because that’s what we defined the interface to be.

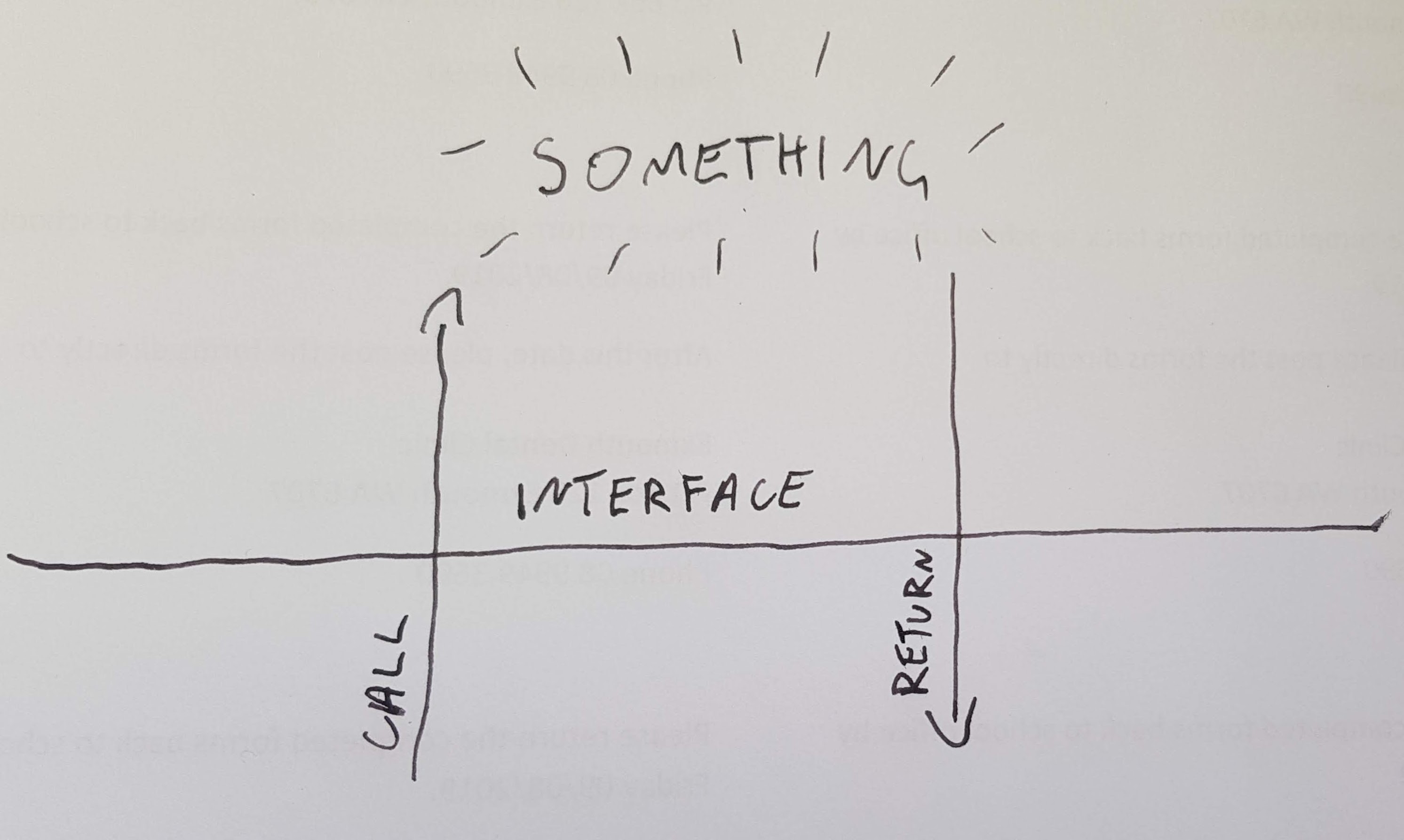

Code from the safe zone can call code in the danger zone, but it must go through the interface. When the code from the danger zone returns, A must be valid. It must be valid because that’s how we defined our interface. In between, A could be made invalid temporarily, as long as when we return to the safe zone, we have a valid A.

A function that we can call from the safe zone interface but exists inside the danger zone, we will call a public function. A public function is allowed to assume that the entity is valid when it starts, and has a responsibility to ensure that the entity is valid when it exits.

So now we have some idea of what an interface is. Let’s talk about encapsulation. Let’s say that we want to make the danger zone as small as possible so that the amount of code that can break A is minimised. I’ll define encapsulation as an attempt to make the danger zone as small as reasonably possible.

If the danger zone extends out forever and encompasses our entire program, then we always have to worry if we might break A by accident when we write code. We don’t want to worry about breaking every other part of our program when we modify any other part. That’s too much thinking. If we make the danger zone small, then we only have to worry about breaking A when we’re inside it.

We’ll also introduce one more definition. The definition of a reference. Let’s say we have two entities, a parent and a child. If you can break the parent by modifying the child or making it invalid, we say that the parent holds a reference to the child. We’ll define a reference this way whether or not an entity holds a physical pointer to the other entity. I might get slack and say that an entity “knows about” another.

In this article we will only deal with the case where there are no circular references.

Shared mutability

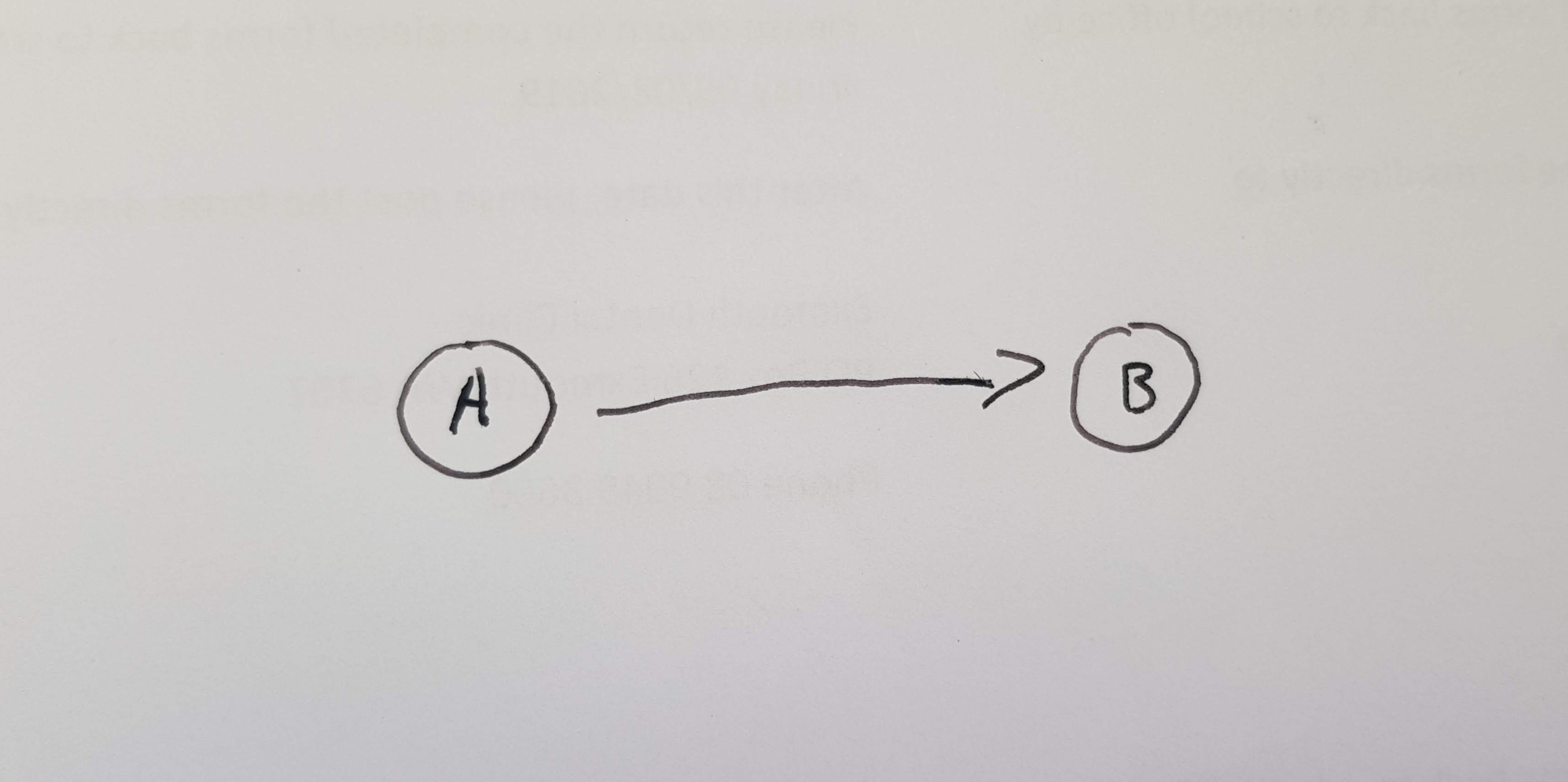

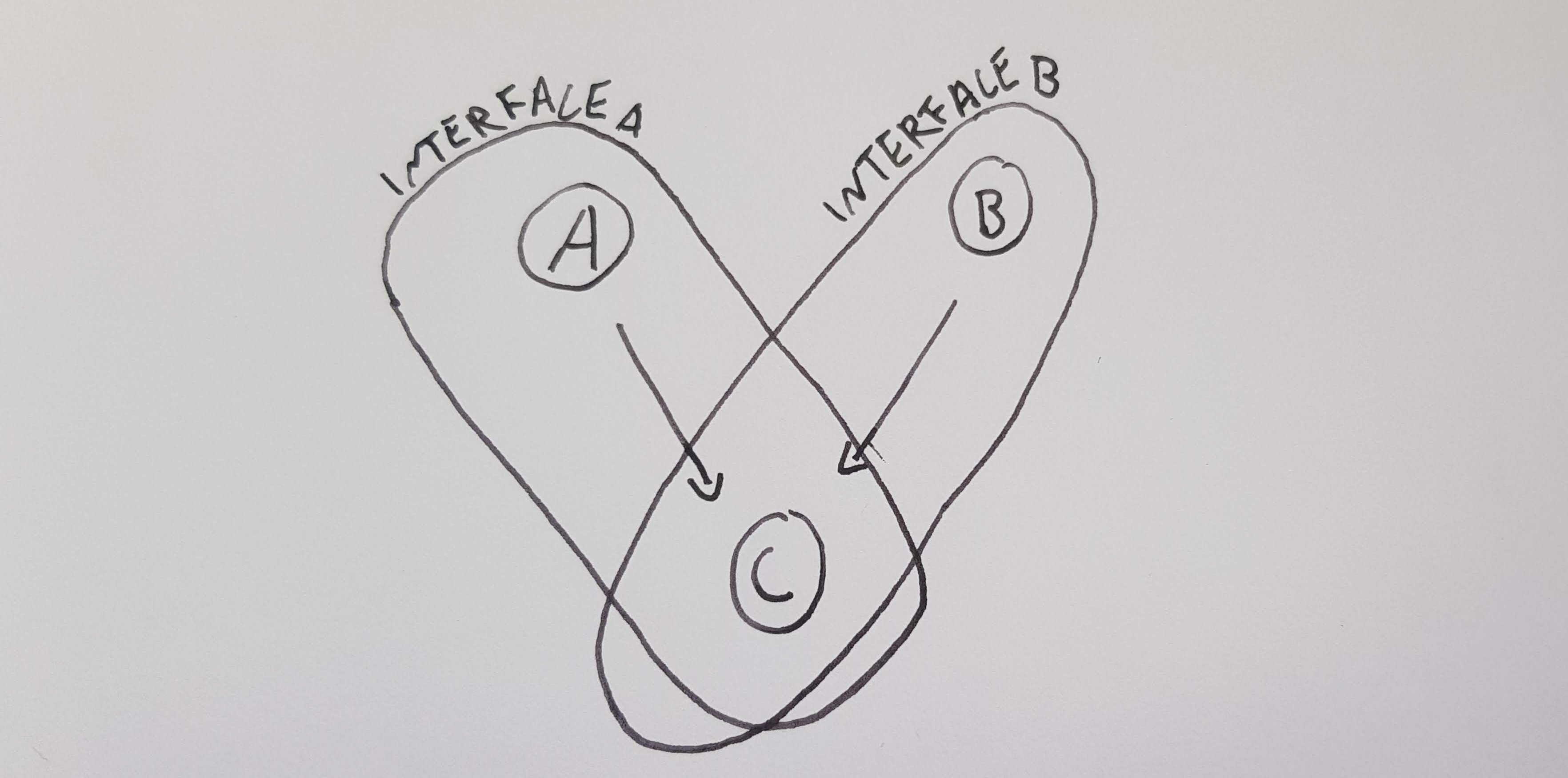

Consider that we have two entities in out program A and B. A knows about B, but B doesn’t know about A. We’ll draw this like so:

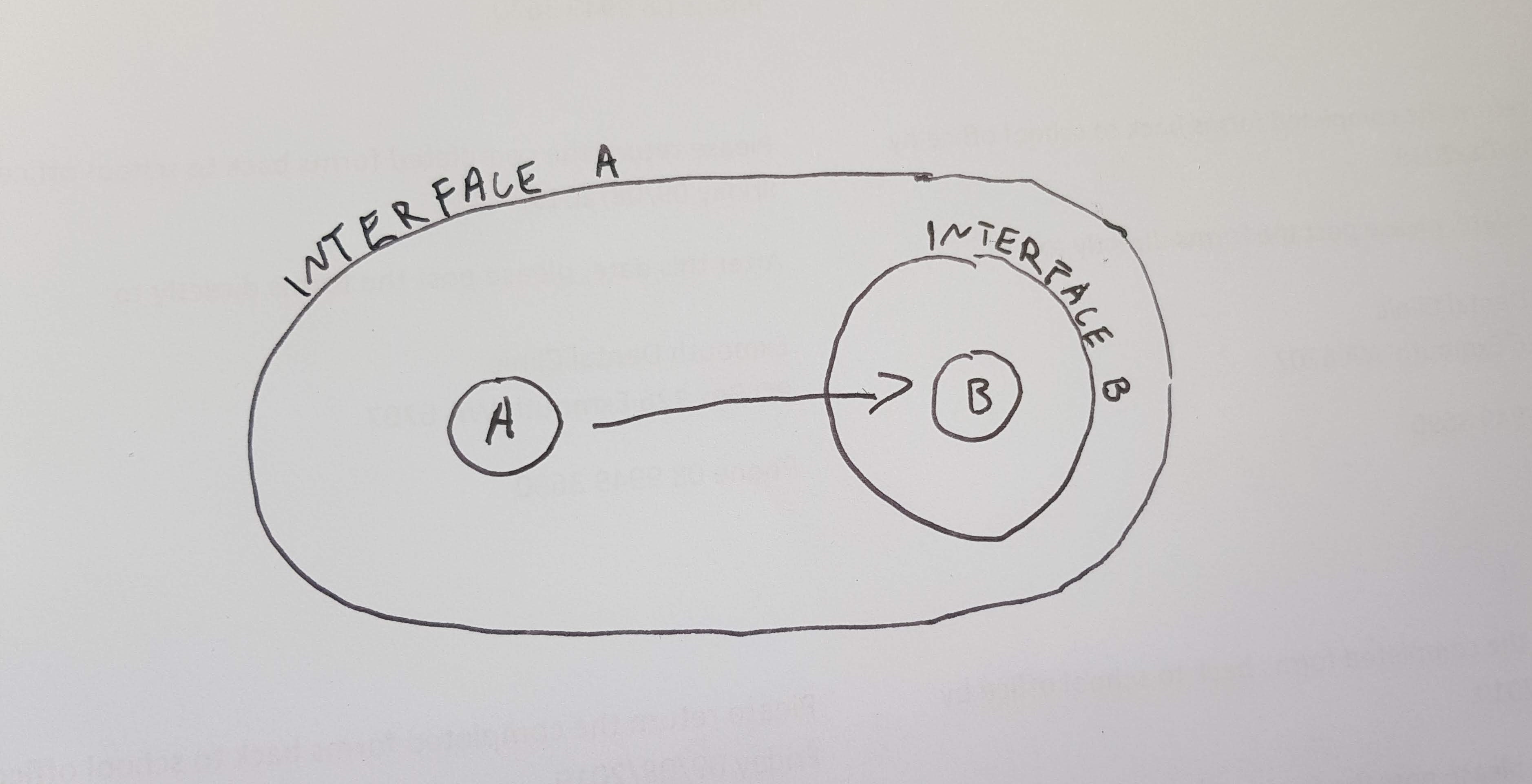

B doesn’t know about A, so the interface for B could just be around B. The opposite is not true. A knows about B and could be made invalid if B were invalid. To encapsulate A, we must surround the danger zone for B as well.

We can now figure out the correct size for the interface for any entity using the following rules.

- The danger zone for

AcontainsAitself. - If an entity

Aknows about another entityB, then the danger zone forAincludes the danger zone forB. - If an entity

Adoes not know about another entityB, thenBis outside the danger zone forA, becauseBcan’t makeAinvalid by our definition of a reference.

We have a problem with shared mutability. Consider two objects A and B which do not know about each other, but have a shared child called C that they both know about. The danger zone for A encompasses A and C, and the danger zone for B encompasses B and C. Because A and B don’t know about each other, they don’t belong in each other’s danger zones. If it were possible that B could cause A to break, then it would imply that A knows about B: a contradiction.

Now we can see this issue. The interfaces of A and B cross over. In order to modify C we must go into both the danger zones for A and B first. Potentially we have a situation where A could modify C and make B invalid, or vice versa. This problem only becomes worse if we have more parents. We will discuss two ways to manage this issue.

Example problem.

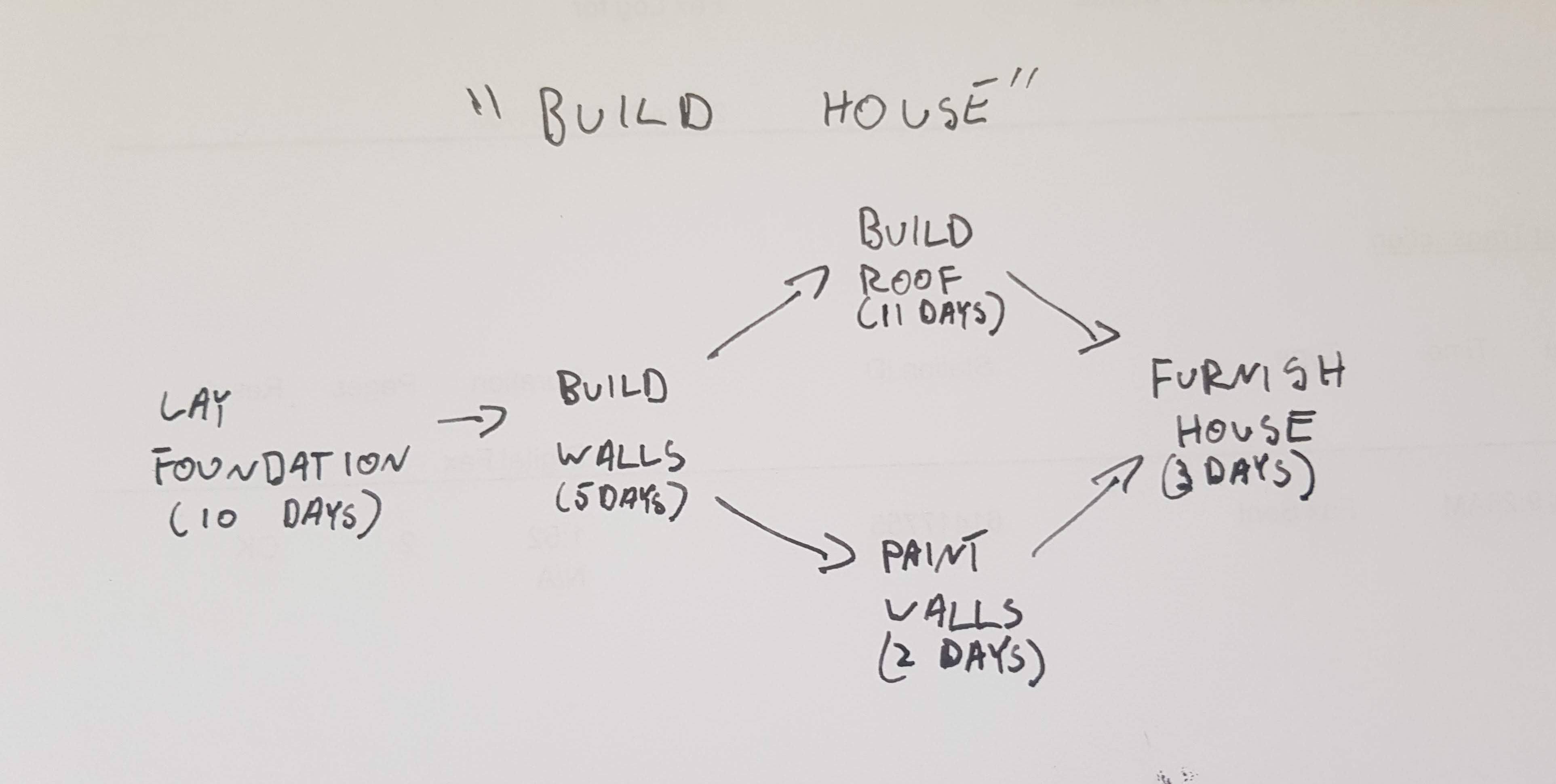

For the purposes of this article we will look at a series of entities called tasks. Each task has a duration (in days) and a name. A task can only be completed after all of its dependencies have been completed. A task with no dependencies starts straight away. For this article, We’ll use the following example:

Solution 1: Freeform shared mutability.

In safe rust, we can share ownership using Rc. This means we don’t have to worry about how long something is going to live for; it will automatically be dropped when nothing else references it. To have shared mutability in a single threaded context, we can use RefCell. If we combine the two we can generate arbitrary graph like structures which have shared mutability. I mention this implementation for completeness, and advise that with almost certainty a RefCell inside of an Rc is an anti-pattern.

We begin by defining our data type. It has a name, duration, and a list of dependencies. We wrap this all up inside our Rc, RefCell sandwich:

use std::cell::RefCell;

use std::rc::Rc;

#[derive(Clone, Eq, PartialEq, Debug, PartialOrd, Ord)]

pub struct InnerTask {

name: &'static str,

duration: u32,

dependencies: Vec<Task>,

}

#[derive(Clone, Eq, PartialEq, Debug, PartialOrd, Ord)]

struct Task(Rc<RefCell<InnerTask>>);

We have seen from the previous part that we cannot have shared mutability and this idea of “internal consistency” simultaneously. This means that we are forced to calculate, on the fly any result that depends on children. We solve the danger zone problem by asserting that the parent isn’t allowed to care what the child’s value is, only that it has a value. This is important if we want to use a RefCell based implementation:

impl Task {

fn new (name: &'static str, duration: u32, dependencies: Vec<Task>) -> Self {

Task(Rc::new(RefCell::new(InnerTask {

name: name,

duration: duration,

dependencies: dependencies,

})))

}

fn set_duration (&self, duration: u32) {

self.0.borrow_mut().duration = duration;

}

fn start_time (&self) -> u32 {

(&self.0.borrow().dependencies)

.into_iter()

.map(|dependency| dependency.end_time())

.max()

.unwrap_or(0)

}

fn end_time(&self) -> u32 {

self.start_time() + self.0.borrow().duration

}

}

The start time of a Task is the maximum of all of its children’s end times. The end time is just the start time plus the duration of the task.

As you can see, start_time accesses every dependency in turn to get a result. In our small example this will be trivial, but in more complicated graphs, we could perform an exponentially increasing number of calls. We are not allowed to cache the results, because some other part of our program could modify one of the other tasks, and make the start and end times invalid.

This is a simple implementation. I provide no methods to modify dependencies; with a RefCell inside an Rc, we have to be careful about creating circular references. We limit ourselves to only creating a Task using older Tasks.

fn main () {

let lay_foundation =

Task::new("Lay Foundation", 10, vec![]);

let build_walls =

Task::new("Build Walls", 5, vec![lay_foundation.clone()]);

let build_roof =

Task::new("Build Roof", 11, vec![build_walls.clone()]);

let paint_walls =

Task::new("Paint Walls", 2, vec![build_walls.clone()]);

let furnish_house =

Task::new("Furnish House", 3, vec![build_roof.clone(), paint_walls.clone()]);

println!("Days require to finish house: {}", furnish_house.end_time());

}

This works, but I don’t recommend it. It is up to the programmer to guarantee that we never cache the results of any of our calculations, however tempting it may be. In addition, this is asymptotically slow. The start and end time for lay_foundation has to be calculated multiple times. In more complicated examples, it may have to be calculated an exponential number of times.

Solution 2: An Arena.

The previous example has shared mutability, but no “internal consistency”. However, if we limit the spread of mutable references to entities that we trust not to break our structure, we can cache the results as much as we like. All the nodes themselves must be “trusted” since they could have a reference to any other node, and we can only give mutable references to “trusted” entities.

In order to create a place where only trusted entities can modify our nodes, we have to create an interface. Inside the interface, we have trusted code, and outside, we have everything else. We call the entity that holds the interface P.

We don’t allow P to hand out mutable references to individual nodes to the safe zone, because outside of P isn’t trusted not to break our structure by our definition of P. P must therefore have exclusive write access to all of the individual nodes. Considering that P is an entity with an interface, that has exclusive write access to its individual nodes, we can say P is an arena.

You might note that I don’t say that P an object. P could be anything. It could be a struct, and enum, a combination of objects or any other entity that could be defined. I only state that whatever P is, it happens to have two properties: all code inside P is trusted not to break it, and it has exclusive mutable access to all of its nodes.

Like the previous article, in order to solve our shared mutability problem, we get rid of the sharing part, and say that all mutable access is through public functions for P.

Note that in order to cache the results of calculations we must have an interface and its associated entity P, and we know that P must have exclusive write access to its members. An arena is not the “best” way of solving the problem of mutability with internal consistency, it’s the only way. Einstein said to make things “as simple as possible, but no simpler”. Although an arena may not be simple, it is the simplest way to write our code whilst remaining correct.

To implement this, we can create a Graph data structure which is just a collection of nodes with unique id’s. A GraphNode contains some data, and a set of incoming and outgoing edges.

use std::collections::{HashMap, HashSet};

use std::hash::Hash;

use uuid::Uuid;

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Eq, PartialEq)]

struct GraphNode<T> {

data: T,

incoming: HashSet<Uuid>,

outgoing: HashSet<Uuid>,

}

impl<T> GraphNode<T> {

fn new (data: T) -> Self {

GraphNode {

data: data,

incoming: HashSet::new(),

outgoing: HashSet::new(),

}

}

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

pub struct Graph<T: Eq + Hash> (

HashMap<Uuid, GraphNode<T>>

);

This is a very simple implementation of a graph. We have some basic functionality that I will brush over for the most part revolving around adding, deleting and querying nodes. There are more efficient implementations, but they are not relevant to this article:

impl<T: Eq + Hash> Graph<T> {

pub fn new() -> Self {

Graph(HashMap::new())

}

pub fn add_edge(&mut self, start: &Uuid, end: &Uuid) {

self.0.get_mut(start).map(|node| {

node.outgoing.insert(*end);

});

self.0.get_mut(end).map(|node| {

node.incoming.insert(*start);

});

}

pub fn remove_edge(&mut self, start: &Uuid, end: &Uuid) {

self.0.get_mut(start).map(|node| {

node.outgoing.remove(end);

});

self.0.get_mut(end).map(|node| {

node.incoming.remove(start);

});

}

pub fn remove_node(&mut self, node_id: &Uuid) -> T {

let node = self.0.remove(node_id).expect("remove_node: invalid key");

for start in node.incoming.iter() {

self.0.get_mut(start).map(|start_node| {

start_node.outgoing.remove(node_id);

});

}

for end in node.outgoing.iter() {

self.0.get_mut(end).map(|end_node| {

end_node.incoming.remove(node_id);

});

}

node.data

}

pub fn add_node(&mut self, node: T) -> Uuid {

let key = Uuid::new_v4();

self.0.insert(key, GraphNode::new(node));

key

}

pub fn get(&self, key: &Uuid) -> &T {

&self.0.get(key).expect("get: invalid key.").data

}

pub fn get_outgoing(&self, key: &Uuid) -> &HashSet<Uuid> {

&self.0.get(key).expect("get_outgoing: invalid key.").outgoing

}

pub fn get_incoming(&self, key: &Uuid) -> &HashSet<Uuid> {

&self.0.get(key).expect("get_incoming: invalid key.").incoming

}

}

We implement our actual Task struct which contains name and duration fields and nothing else. One of the advantages of using an arena is that we can separate the data that represents relations between nodes from the nodes themselves. This means that a node can therefore uphold its own invariants that don’t depend on it being part of a larger structure:

#[derive(Clone, Eq, PartialEq, Hash, Debug, PartialOrd, Ord)]

pub struct Task {

name: &'static str,

duration: u32,

}

impl Task {

fn new (name: &'static str, duration: u32) -> Self {

Task {

name: name,

duration: duration,

}

}

}

Like the previous article, we create a “view” of the graph, that freezes it temporarily. This allows us to cache the results of calculations as much as we like. When we modify any of the nodes, or the structure of the graph, we have to discard the cache because it’s no longer valid. The view struct contains a cache of start times and end times:

struct GraphView<'a> {

graph: &'a Graph<Task>,

start_times: HashMap<Uuid, u32>,

end_times: HashMap<Uuid, u32>,

}

If we wanted to cache the results we can use a little bit of boilerplate and write something like the following:

impl<'a> GraphView<'a> {

fn new (graph: &'a Graph<Task>) -> Self {

GraphView {

graph: graph,

start_times: HashMap::new(),

end_times: HashMap::new(),

}

}

fn end_time(&mut self, key: &Uuid) -> u32 {

// Boilerplate

if let Some(result) = self.end_times.get(key) {

return result.clone();

}

// Actual query

let result = self.graph.get(key).duration + self.start_time(key);

// Boilerplate

self.end_times.insert(key.clone(), result);

result

}

fn start_time(&mut self, key: &Uuid) -> u32 {

// Boilerplate

if let Some(result) = self.start_times.get(key) {

return result.clone();

}

// Actual query.

let result = self.graph.get_incoming(key)

.into_iter()

.map(|key_out| self.end_time(key_out))

.max()

.unwrap_or(0);

// Boilerplate

self.start_times.insert(key.clone(), result);

result

}

}

The boilerplate simply checks if we have already calculated the value. If we have, we just return the value, otherwise, we calculate the value, and insert the result into the HashMap. This is actually just depth first search in disguise.

This allows us to write any kind of graph traversing query in a declarative manner. We can write what we want the result to be based on other nodes in the graph and not have to worry about the actual execution of the query.

Mind you that this implementation is asymptotically efficient for both read heavy and write heavy use cases. In read heavy implementations, we cache the results of intermediary calculations, and lazily perform the minimal number of steps required to produce a result. In write heavy loads, we discard the cache entirely, and only have to update the essential data in the individual nodes themselves, and nothing else.

We can use the graph like the following:

fn main() {

let mut graph = Graph::new();

let lay_foundation = graph.add_node(Task::new("Lay foundation", 1));

let build_walls = graph.add_node(Task::new("Build walls", 2));

graph.add_edge(&lay_foundation, &build_walls);

let build_roof = graph.add_node(Task::new("Build roof", 4));

graph.add_edge(&build_walls, &build_roof);

let paint_walls = graph.add_node(Task::new("Paint walls", 8));

graph.add_edge(&build_walls, &paint_walls);

let furnish_house = graph.add_node(Task::new("Furnish house", 16));

graph.add_edge(&paint_walls, &furnish_house);

let mut view = GraphView::new(&graph);

println!("Days require to finish house: {:?}", view.end_time(&furnish_house));

}

This solution is verbose, but has strong guarantees. We can extend this structure in multiple ways. If we need nodes of different types, we can have one collection of nodes for each type inside our Graph structure. If we need different kinds of connections between nodes, we can modify our GraphNode structure to have more fields than just incoming and outgoing. We can even detect cycles if we modify the view code slightly:

struct GraphView2<'a> {

graph: &'a Graph<Task>,

// Store an Option rather than the value itself.

// None means a circular reference

start_times: HashMap<Uuid, Option<u32>>,

end_times: HashMap<Uuid, Option<u32>>,

}

impl<'a> GraphView2<'a> {

fn new (graph: &'a Graph<Task>) -> Self {

GraphView2 {

graph: graph,

start_times: HashMap::new(),

end_times: HashMap::new(),

}

}

fn end_time(&mut self, key: &Uuid) -> Option<u32> {

if let Some(result) = self.end_times.get(key) {

return result.clone();

}

// We assume that a node is part of a circular reference

// until proved otherwise.

self.end_times.insert(key.clone(), None);

let result = self.start_time(key)

.map(|time| time + self.graph.get(key).duration);

self.end_times.insert(key.clone(), result);

result

}

fn start_time(&mut self, key: &Uuid) -> Option<u32> {

if let Some(result) = self.start_times.get(key) {

return result.clone();

}

self.start_times.insert(key.clone(), None);

let result = self.graph.get_incoming(key)

.into_iter()

.map(|key_out| self.end_time(key_out))

.fold(Some(0), |max_time, end_time| Some(max_time?.max(end_time?)));

self.start_times.insert(key.clone(), result);

result

}

}

In this example start_time and end_time return None if the nodes are part of a circular reference, so we can detect them and handle them accordingly.

Conclusion

I present two ways to construct code that has shared mutability in some kind of arbitrary acyclic graph structure in Rust. On one hand we have a freeform structure which involves Rc and RefCell. The disadvantage of this kind of structure is that we cannot cache results that depend on other entities. In addition, we have to be careful not to introduce reference cycles. It appears simple but has some complicated caveats.

On the other hand, we can create some kind of arena. I provide an example implementation: a graph. I can separate the data that represents relations between nodes from the data of the nodes themselves. The graph can be temporarily frozen to mutation so we can perform queries. It does not use RefCell, so it has stronger static guarantees regarding borrowing. It is asymptotically efficient for a variety of use cases. We can write declarative queries and have them efficiently executed. It can also be extended in a variety of manners. It is my opinion that this is the simplest “correct” implementation.

In the next article, I will discuss structures which contain reference cycles.

This post was originally posted on Andrew’s Notepad

Rust

graph

acyclic

mutability

references