What is an invariant?

- The specification of a program should be its class invariants

- Aim to write programs so that you cannot create invalid objects or data.

I’ll use Rust as the language to describe the concepts behind this post, but try to make it accessible to those using other languages.

We can start with a simple object, such as a circle. A circle is completely defined by it’s radius. As long as our radius is positive, we have a valid circle:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Circle {

radius: f64

}

impl Circle {

fn new_option (radius: f64) -> Option<Circle> {

if radius > 0.0 {

Some(Circle {radius: radius})

}

else {

None

}

}

fn new_assert (radius: f64) -> Circle {

assert!(radius > 0.0);

Circle {radius: radius}

}

}

For this example, we have two constructors: new_option and new_assert. They are two versions of the same constructor. The new_assert function takes a radius, returns a circle if the radius is positive, and kills the program if it is not. The new_option function takes a radius, returns a circle if the radius is positive, and returns nothing if it is not. Discussion on which method is more appropriate to use is left for another time.

It is impossible to create a circle with a negative radius if we can only use new_option or new_assert. Seeing as we have no functions available to modify a circle once we have created it, we can safely assume that every circle we encounter in our program will always have a positive radius. A positive radius is therefore an invariant of a circle.

We can extend our program to be able to modify a circle:

impl Circle {

// Constructors.

fn grow (&mut self, length: f64) {

self.radius += length;

}

fn shrink (mut self, length: f64) -> Option<Circle> {

if self.radius - length > 0.0 {

self.radius -= length;

Some(self)

}

else {

None

}

}

}

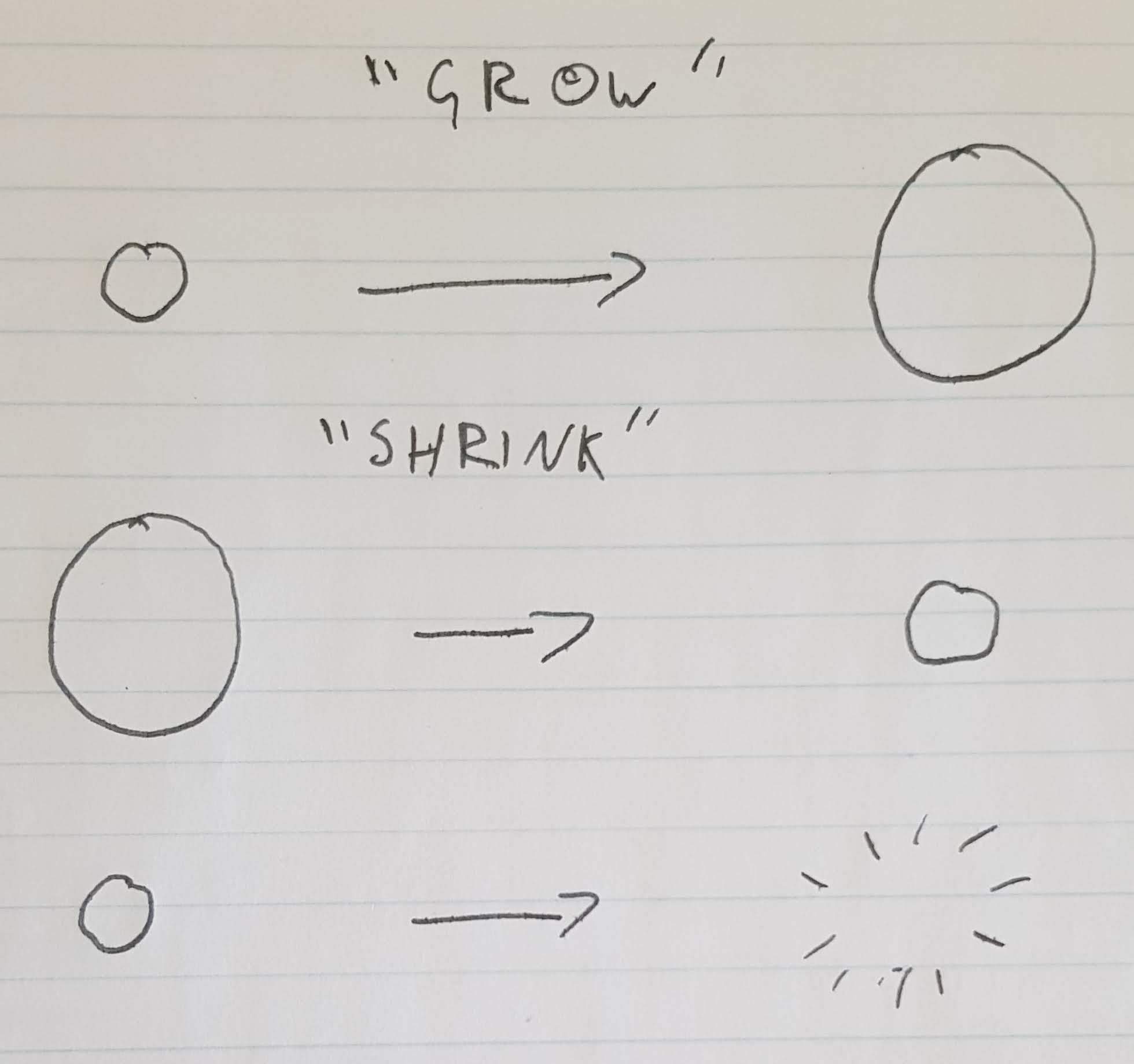

We create two functions grow and shrink. The grow function increases the radius of a circle by length and the shrink function reduces the radius of a circle by length. grow is easy. Simply add the length to the radius. If we start off with a valid circle, then make the radius bigger, it will still be valid. shrink is more difficult. If we are going to make the radius smaller, we have to check that it doesn’t become negative. If it becomes negative we destroy the circle. We have to destroy the circle otherwise it will no longer be valid.

With a little bit of logic we can make some conclusions:

- We can only construct valid circles using

new_assertornew_option. - If we have a valid circle and we modify it using

grow, the result will be also be valid. - If we have a valid circle and modify it using

shrink, the result will either be valid, or the result will be destroyed. The rust compiler will ensure that we cannot use a circle after it has been destroyed. - Therefore, as long as we only use

new_assert,new_option,grow, andshrink, we can not create invalid circles in our program.

Obviously some invariants are going to be more complex than simply having a positive radius, but it goes to show that we can create programs which never invalidate their invariants.

This is the principle behind encapsulation. If we only access the data through a few functions which only produce valid values, we will never encounter invalid values.

We can use a little more logic to reason about bugs in programs:

- If we can prove that a program does what it is supposed to do if it never invalidates its invariants, and

- If we can prove that a program never invalidates its invariants:

- Then we can prove that the program does what it is supposed to do.

Furthermore

- If the only thing a program is supposed to do is not invalidate its invariants, and

- If the program does not invalidate its invariants,

- Then the program is correct.

If we define the behavior of a program (i.e. its specification) as its invariants, then we take care of step one. If we write a program so that it becomes difficult (or impossible) to invalidate invariants, then we take care of step two and our program is then correct.

There are only two sources of bugs if we follow these principles. Either we don’t know what we actually want (i.e. we get the specification wrong and deliberately write the wrong program), or we invalidate our invariants. This way we can narrow down where our bugs come from.

Rust

Trait

Struct

Class

Types

Invariant

Programming